Why We Need Guerilla Marketing

People are pretty good at tuning out advertising these days. The average American could probably walk through Time Square without integrating a single piece of information about a single brand. The modern adaptive mechanism to shut the brain off during television commercials has never been sharper.

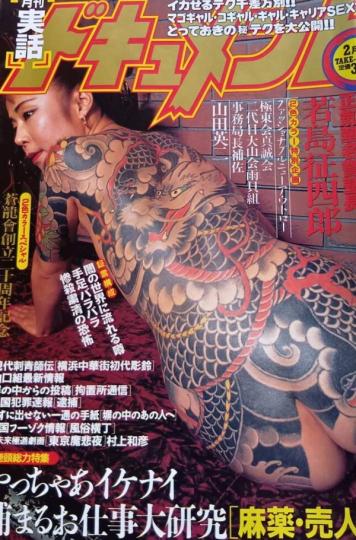

Kill Bill adverts

To combat the weakening marketability of minds, there is guerilla marketing. It has been around basically as long as the normal kind, although it was only coined as an official strategy in the 80s by Jay Conrad Levinson in his book of the same name.

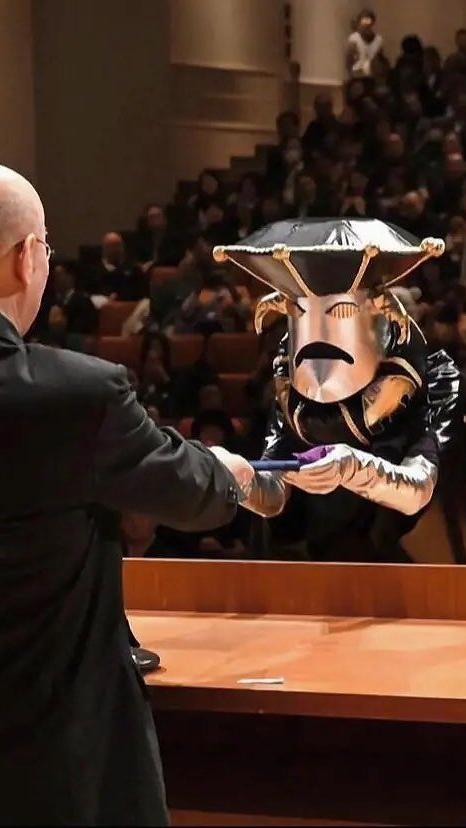

Aphex Twin guerilla effort for the EP Collapse. London's Elephant and Castle tube station.

It’s a category with a loose definition. Inspired by guerilla warfare, it makes us think of a scrappy and unconventional approach, often utilizing surprise and deception, and usually avoiding the mainstream advertising pipelines of television and conventional print.

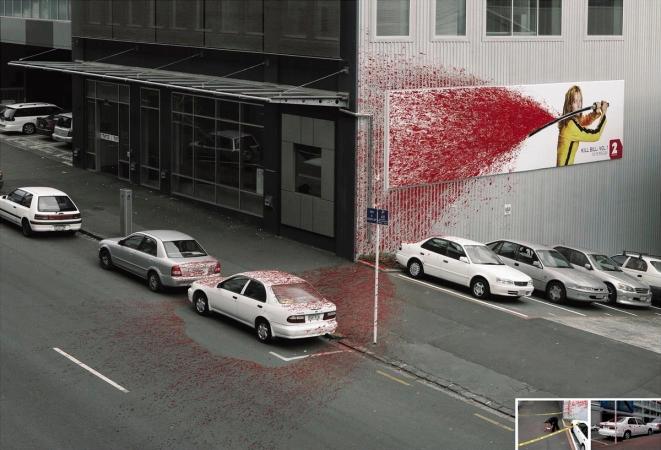

A billboard in Auckland, NZ

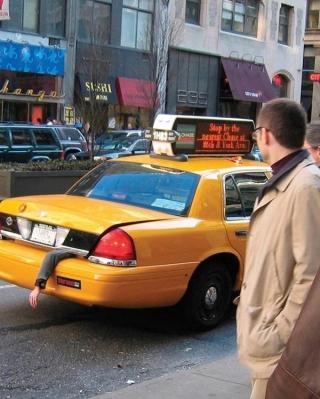

Most of us are familiar with a few examples. Everyone has seen the arm dangling from the taxi trunk and concrete-mounted shoes used to promote the final season of The Sopranos. Kill Bill’s elevator ads, blood-sprayed billboards, and nondescript bloodstains in public restrooms have also been widely documented.

Sopranos guerilla efforts

Movies lend themselves to this sort of thing due to the strong physical component of set design. A few other fun examples: ahead of the Australian release of IT red balloons were tied to sewer grates around Sydney.

IT guerilla balloons

A urinal was mounted 12 feet off the ground in a men's restroom. No good record on whether anyone attempted to use it. Presumably it wasn’t hooked up to any plumbing. Spider Man 2 went on to have a pretty good box office showing.

For Spider-man 2 c. 2004

Not only movies utilize guerilla strategy. Audi replaced movie theater seats with ultra-lux Audi ones to prove a point about comfort. Ikea dropped fully furnished living spaces in public venues. Nike affixed a soccer ball to the side of a building.

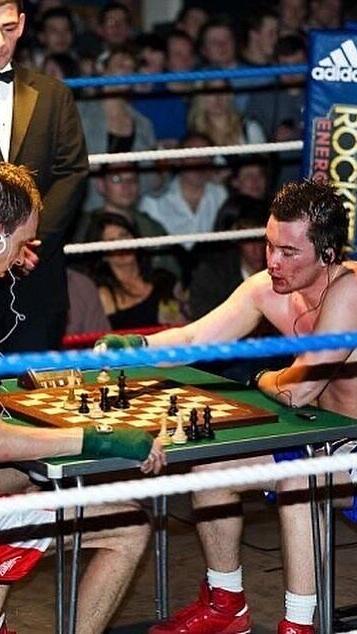

While a billboard can hardly be called 'guerilla' the incorporation of an unexpected dimensions is right out of the playbook

Surprise performances (like Kendrick’s leading up to the TPAB) and even surprise projections (Ye’s Yeezus rollout comes to mind) can be included under the umbrella as well. Aphex Twin’s nondescript perspective-warping posters pasted to subway walls to break news of their album dropping were certainly guerilla.

A Yeezus marketing effort: Ye's face projected on building side

Guerilla campaigns sometimes utilize live talent. 2022 horror film Smile hired two actors to attend three MLB games, sit in very expensive seats directly behind home plate, and smile creepily into the broadcast.

Smile guerilla approach - at an MLB game

A little less theatrical is Red Bull's utilization of professional extreme sport athletes. They frequently enlist daredevils for outrageous stunts under the Red Bull aegis. For their Project Stratos Felix Bumgartner fell 24 miles straight down from an atmospheric balloon, breaking the record for highest ever jump, achieving supersonic speed, and garnering a lot of clicks.

Project Stratos was obviously quite a production, but it required less concrete than the Oreo Vault. Modeled after the Global Seed Vault and built just down the road from it by a Scandinavian architecture firm, the concept was to secure the cookie’s recipe. This might be an important goal if people were able to actually pronounce their ingredients.

Oreo's vault and preservation chambers

Sometimes guerilla efforts backfire. For a Folgers Coffee campaign, New York City manholes were covered with an image of a cup of coffee. The manhole steam made the image look like a hot cup of coffee planted in Big Apple concrete. But it didn’t smell like one, and what it did smell like, presumably, did not conjure warm positive coffee associations. Bosch’s nearly identical concept to promote their irons made a little more sense, scent-wise.

'Manhole' c. 2006

Sometimes the goal is pure deception. Like the Korean beef restaurant that printed LV patterns on the back of their fliers, folded them to look like wallets, and left them scattered around on the sidewalk. Or the pizza restaurant that did the same but with euros peeking out.

What appeared to be a windfall turns out to be a coupon

Sometimes there is fire involved. Double Grill and Bar in Yekaterinburg, Russia, put a photo of a raw steak on a billboard with no branding or additional information. After a day of confused passersby, in the dark of night, a pyrotechnic team used a flamethrower to sear vertical lines into the image, mimicking the effect of a grill grate. Their last act was to expose the restaurant name.

While many of these efforts are low-cost, it’s hard to imagine they return green revenue purely from the people that see them in person. Thus, image-taking is a crucial second-order effect of guerilla campaigns.

This has reached new heights today, with campaigns that seem to rely on being entirely perceived through photographs. Yeat’s 2093 rollout included the use of a fallow crop field in Kansas, massively emblazoning the 2093 symbol. Basically nobody would see this with their own eyes; it was only even visible in its entirety from the air above.

Aerial view of Yeat's 2093 advert

To get even more nebulous, sometimes guerilla efforts are not about any new visual at all. They instead attempt to insert themselves into discourse. The whole Barbenhiemer thing was synthesized rivalry to pump the movies into popular discussion. And look how that worked.

Unsuspecting moviegoers were treated to a film in Audi seats - there is no available data on the efficacy of this

Today, it is not the gross quantity of attention that counts, but the quality of attention. The things exposed to the most eyes are exactly the things no one sees. Virality today is more a phenomenon of thought than it is exposure. Something is truly viral when it is widely THOUGHT about. The goal is to provoke a cascade of thinking. This is a particular type of attention. Its downstream effect is discourse.

Another Guerilla effort in New Zealand

The best way to get people to think about something is to make them feel special. People want an intimate relationship with the material, an inside track. If everyone saw it, it isn’t worth talking about. But if just you see it, on some random street, on some random day, different story.

It can be hard to tell the difference between liking something and feeling special because you saw it. But that’s our problem, not the marketing team’s.

Image curation by Erild Kondi (@kondierild)