Bruce Davidson's "Circus"

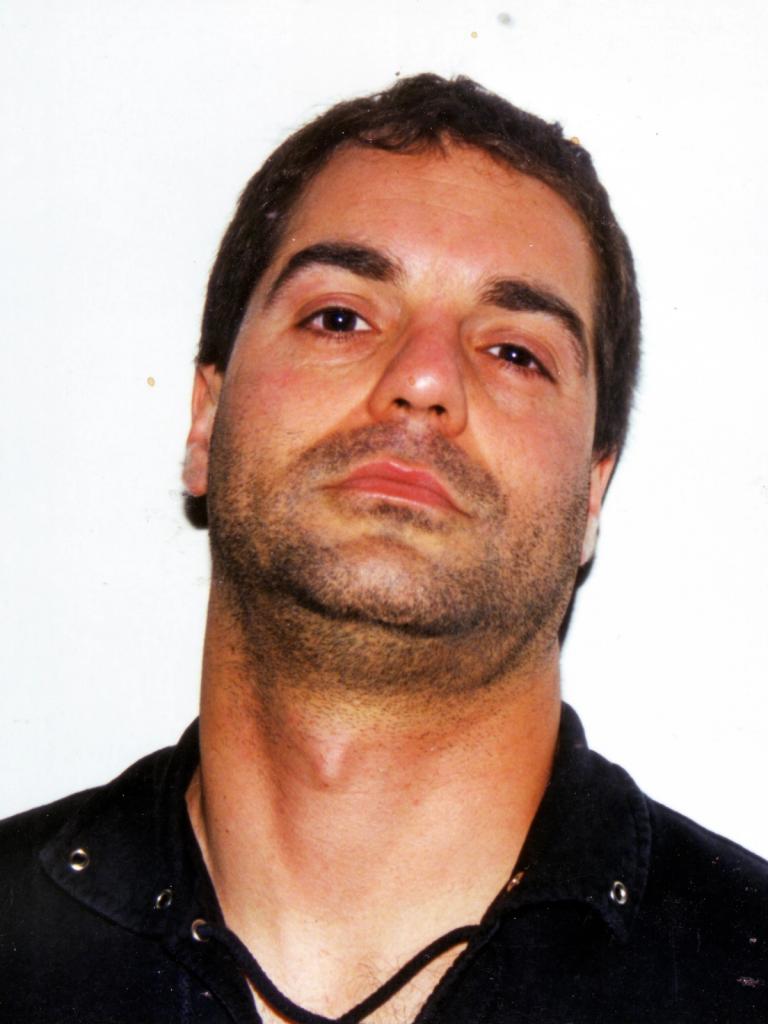

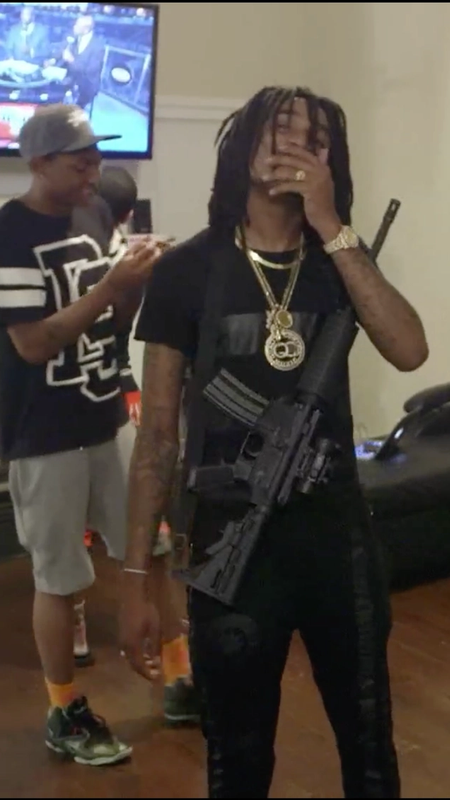

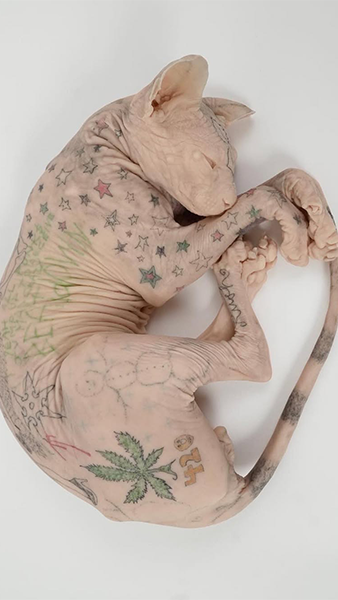

Bruce Davidson was probably always going to be a photographer. At age ten his mother built him a dark room in their suburban basement. For his bar mitzvah he was gifted a camera. A photograph of an owl won him a national award for high school photographers. At Yale, Joseph Albers (a monumental teacher of art) told him his work was too sentimental. Then Davidson was drafted, and ended up in Paris where he took a series of very sentimental photographs of a widow of a French impressionist. These photographs were good enough to be published in Esquire, where they caught the eye of one of Davidson’s heroes, Henri Cartier-Bresson, a less sentimentality-averse man who believed that photography was about capturing a decisive moment.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/f4c9ef5d0d89e6051727f5d492da73aa7bf68b29-1800x2716.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=900)

Henri Cartier-Bresson Derrière la Gare Saint-Lazare 1932 © Henri Cartier-Bresson | Magnum Photos

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/2a2f9fbc57aa7c83dd7cbfdd853e13a7dcc42280-1080x1350.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=540)

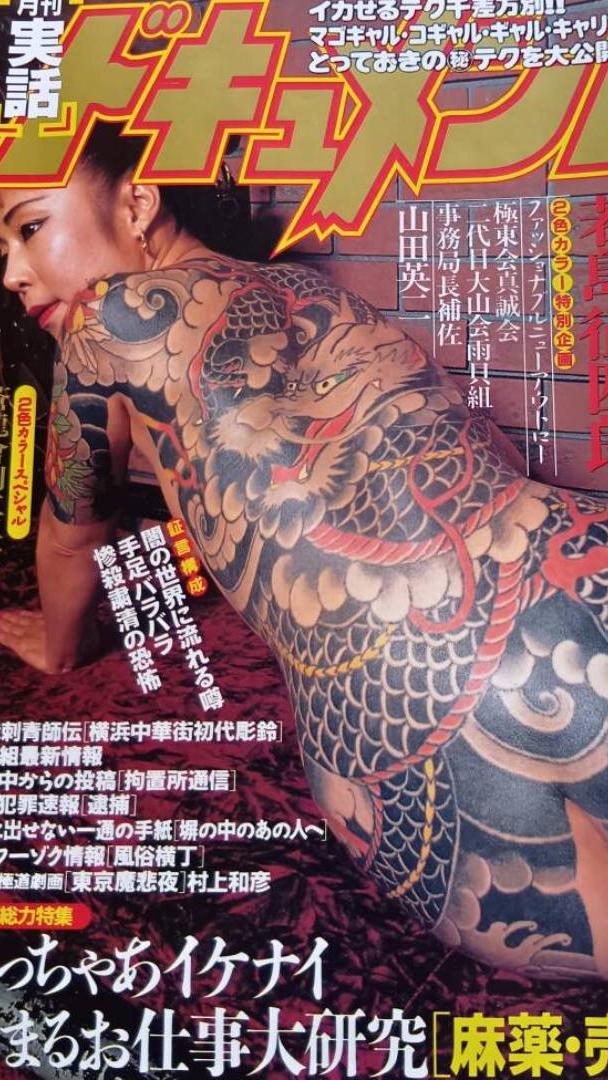

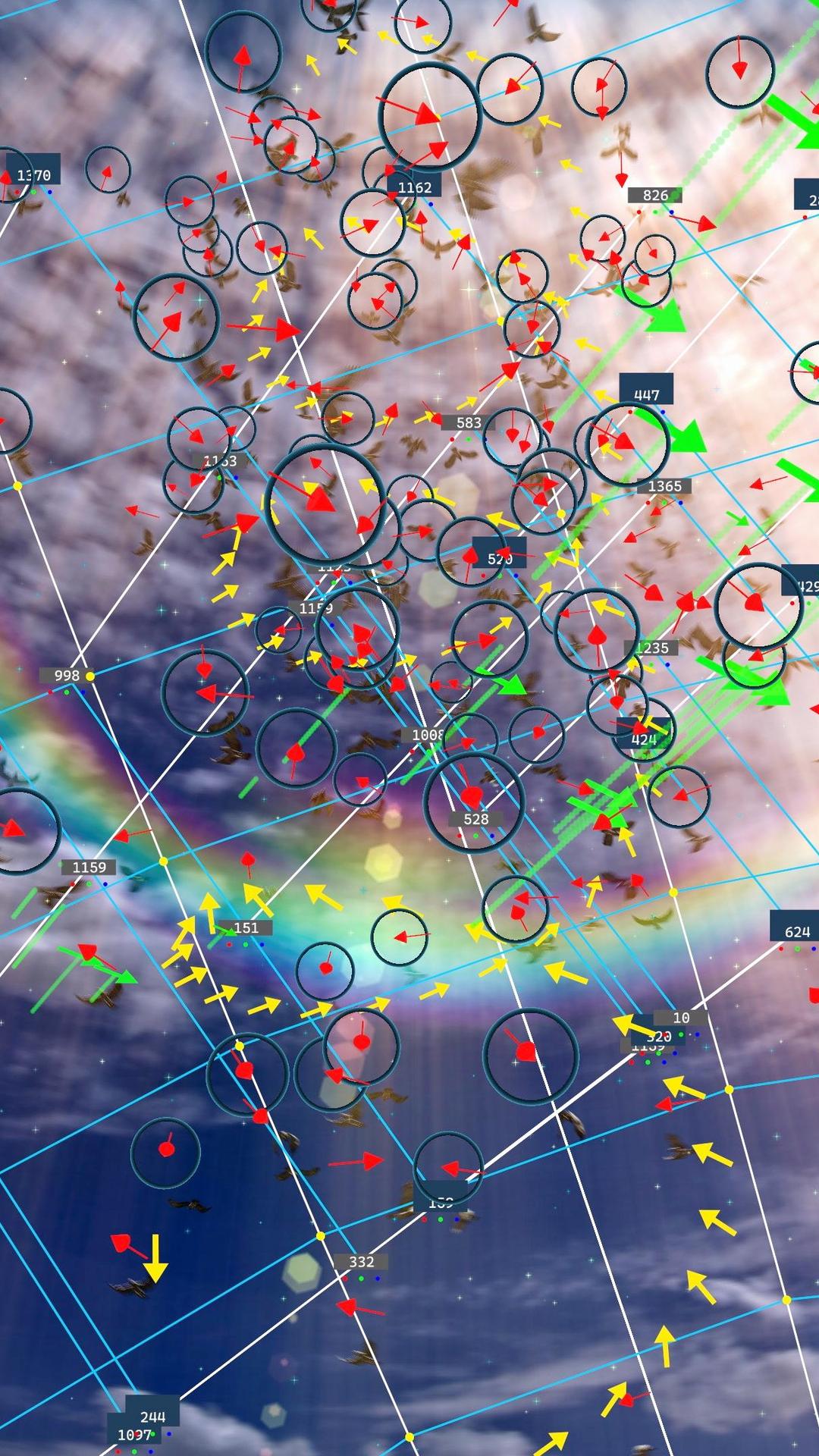

Bruce Davidson, Circus, 1958 © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

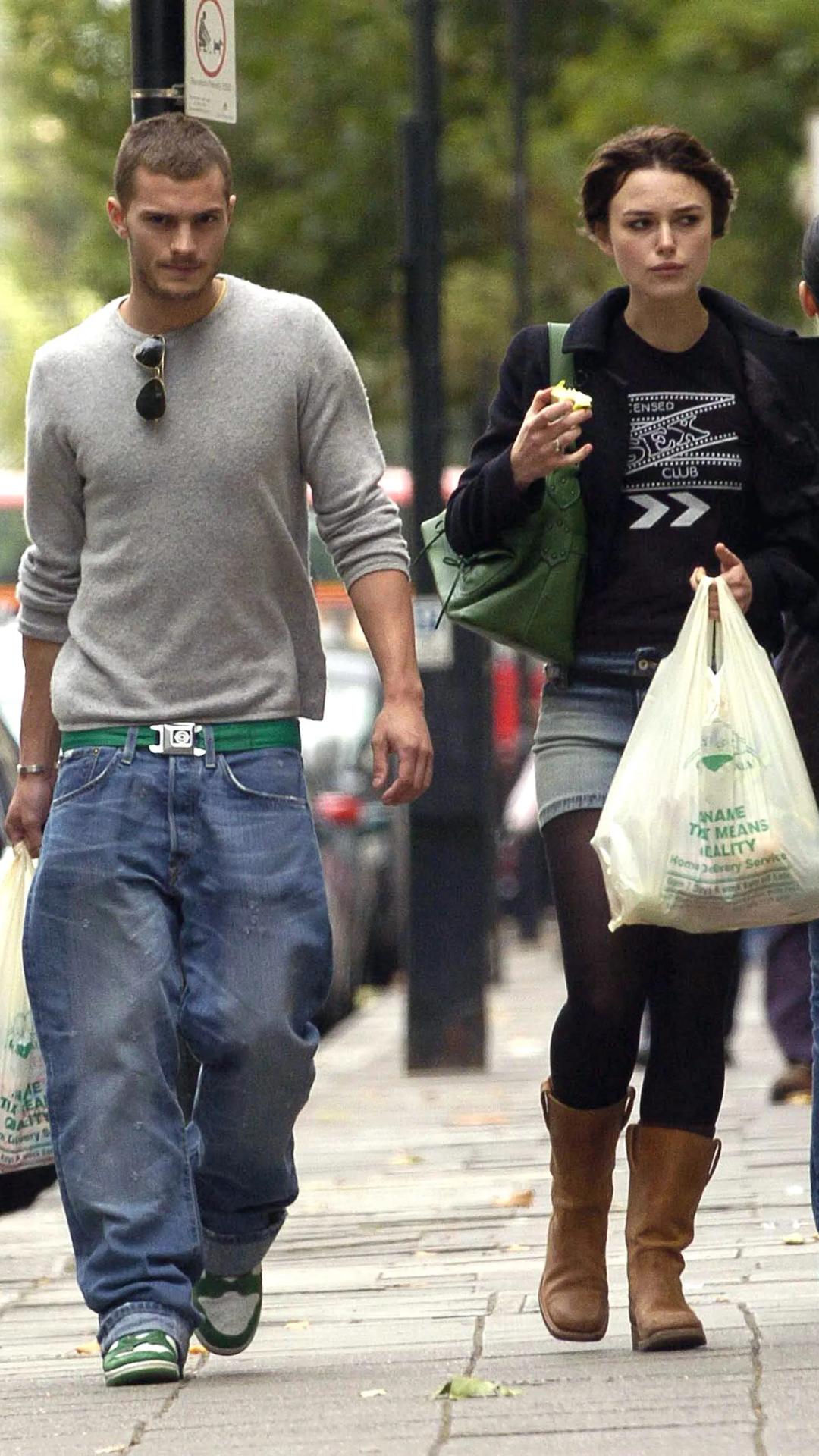

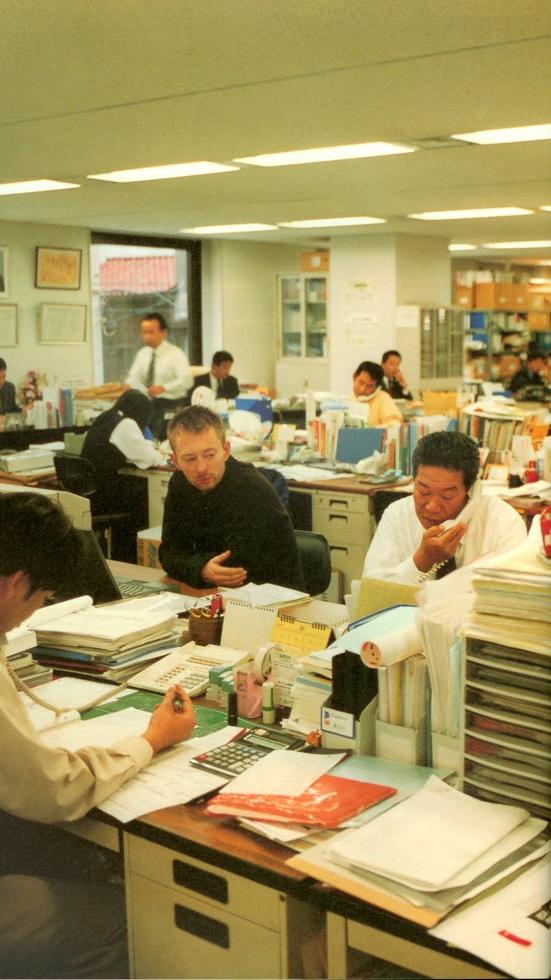

In 1958, aged 25, the still sentimental Davidson visited the Clyde Beatty Circus. He had no connection and wore no press credentials. He walked to the back. There, laundry undulated on clothes lines and performers, resolved back into humanness, sat around, bored, smoking, playing cards. So began “Circus,” a three-installment, decade-spanning, fairly sentimental photo series.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/b2240300217183e30c5338be4e018a15ff4a2d45-1280x856.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=640)

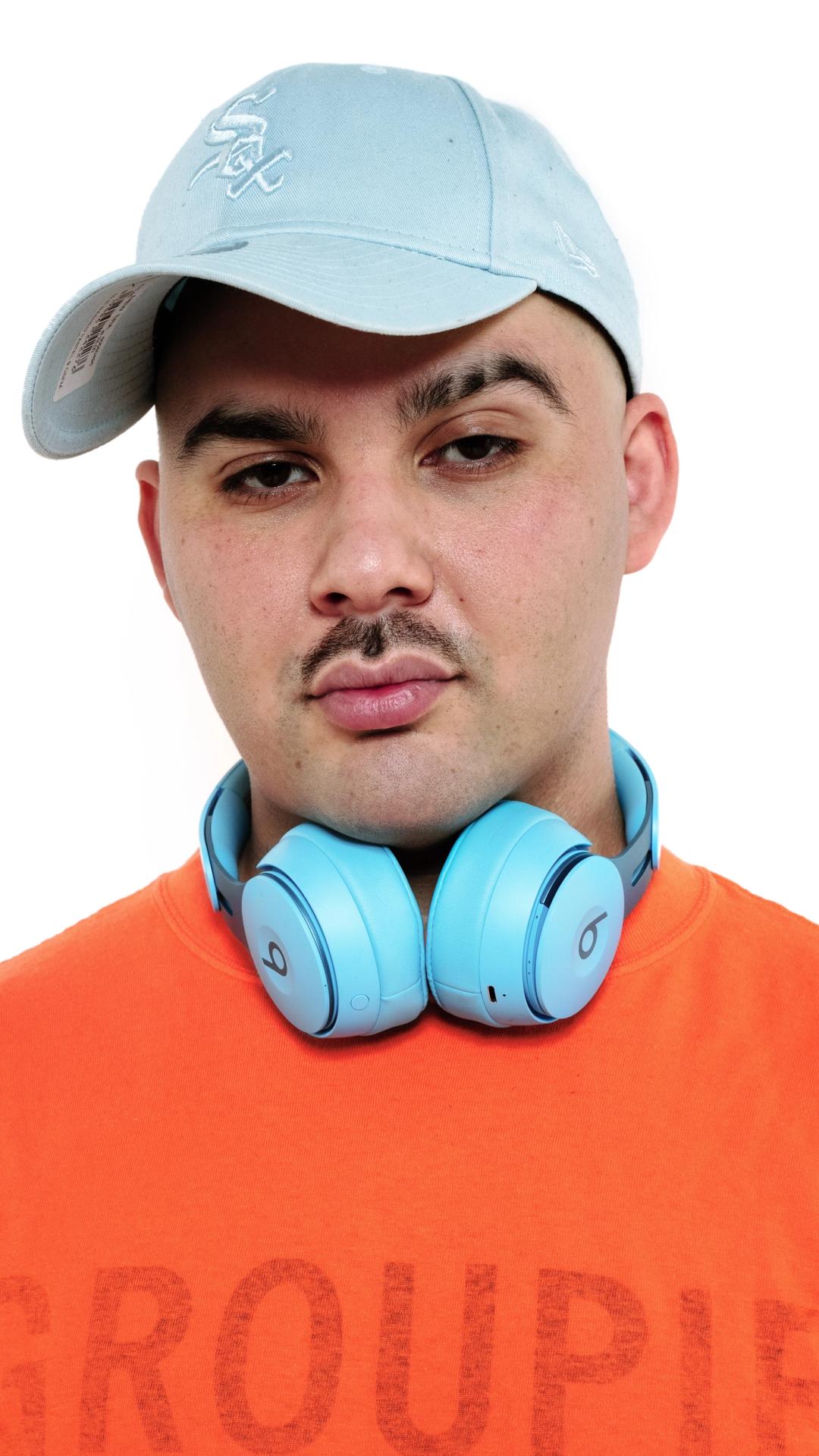

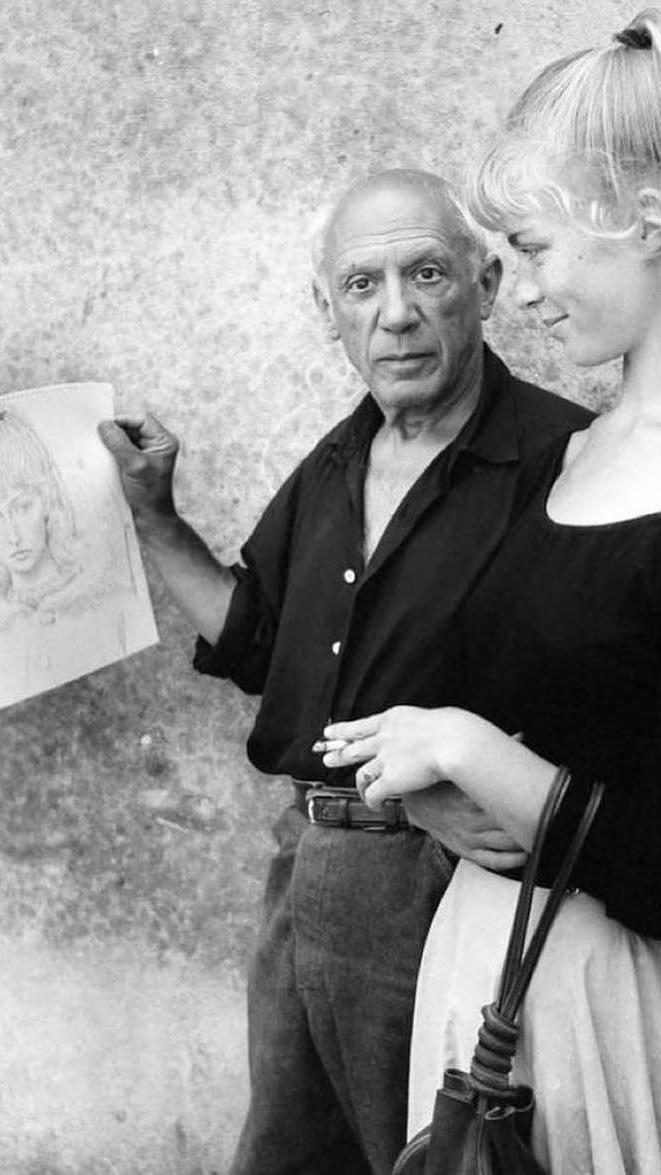

Bruce Davidson, Circus, 1958 © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

Davidson approached the circus through the offstage, the quiet moment, the inner life of the performer. Anyone with a coin could pay to see the performance itself in sharper relief than he was likely to capture with his camera. Davidson was interested in what you couldn’t pay to see. In true Bressonian fashion, he searched for the decisive moment, the one before the mask falls, the one with the cigarette, the one with the vacant look.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/fa8a76470fe4184b48693dd3af95c94044b20c4b-1050x1312.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=525)

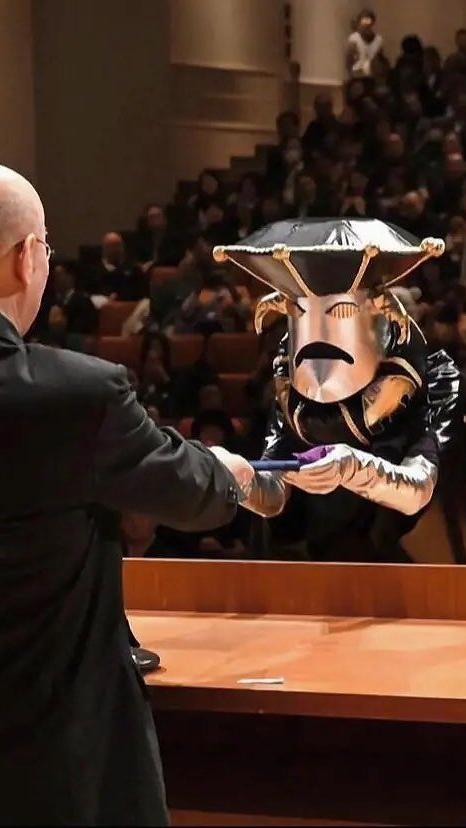

Bruce Davidson, Circus, 1958 © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

The Clyde Beatty Circus was set up at the Palisades Amusement Park in New Jersey. A massive three-ring under-taking, at the time a sort of local draw we don’t contemporarily associate with the circus. Davidson immediately fell on one Jimmy Armstrong, a photogenic dwarf clown whose inner life was the protagonist of the first installment of “Circus.”

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/d832f40e9b78f3b199cdaa6c6d642d977e7ebd6a-1280x830.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=640)

Bruce Davidson, Circus, 1958 © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

Davidson’s style was fit for the time, or even ahead of it. Davidson was an early practitioner of the “New Journalism” that would sweep his field in the 60s and 70s. Both a style and a practice, New Journalism placed priority on subjective portrayal by an integrated reporter, and was part of a much larger cultural reckoning with conventional concepts of perspective, objectivity, and truth.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/b733db48ec362e703f5172b66188d9be859542c8-1080x1350.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=540)

Bruce Davidson, Circus, 1958 © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

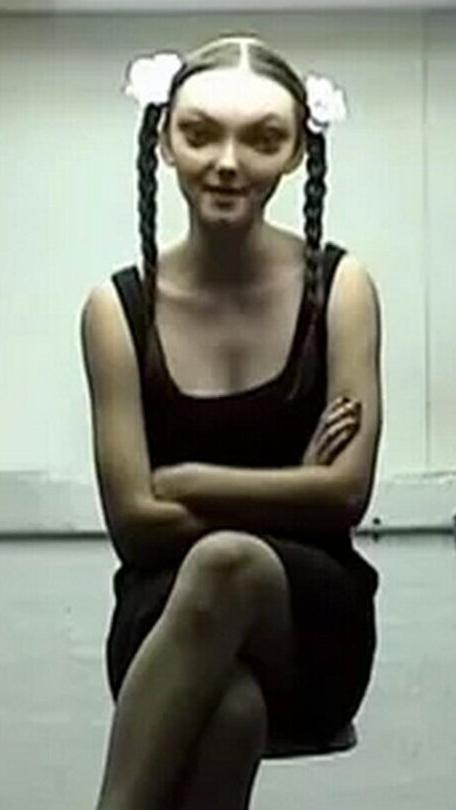

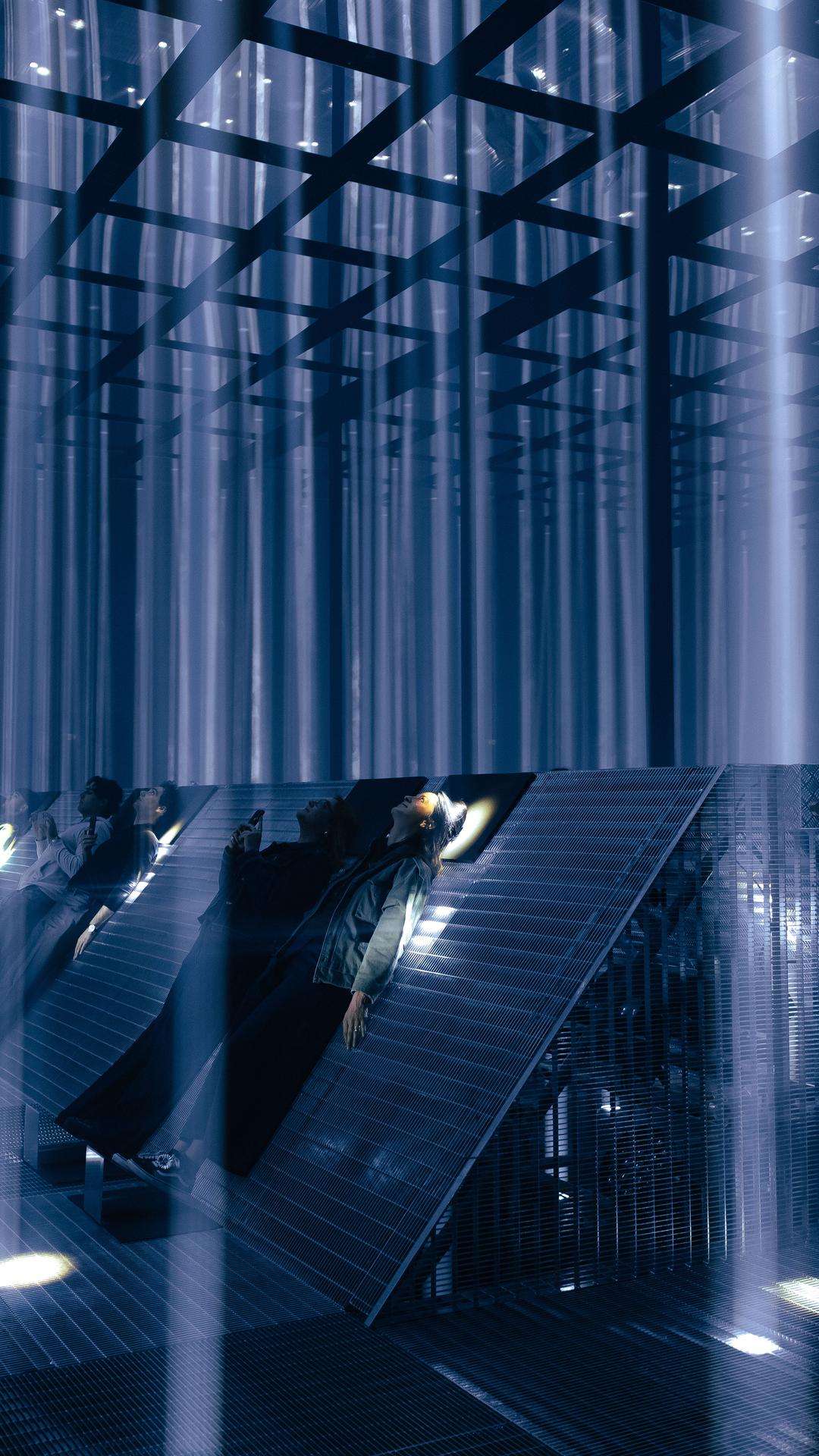

The second installment depicted the Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus in North Carolina in 1965. Crucially, this was an indoor Circus. Here, the ‘offstage’ has a less intimate feel. Elephants are led through truck bays. Acrobats stretch beneath towering bleachers. When captured at all, performance is swallowed by the setting. This is a coliseum. A permanent fixture through which entertainment acts pass, transient. The show is not ‘in’ town; the show is ‘in’ the coliseum, beneath the metal scaffolded ceiling. Saves a fortune on tent canvas, but there are fewer places to pitch a tent or hang a clothes line around an arena.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/f9abe462001b1319ead9aeee5e90b11e20466f07-560x374.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=280)

Bruce Davidson, Circus, 1958 © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

Perhaps it was at this moment that the circus died, the moment when it could no longer host itself. There are also the trends of television, media-proliferation, and the rise of other forms of entertainment.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/66f2e3132eca5953ea742da5b85085e8eafc7e33-1920x1534.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=960)

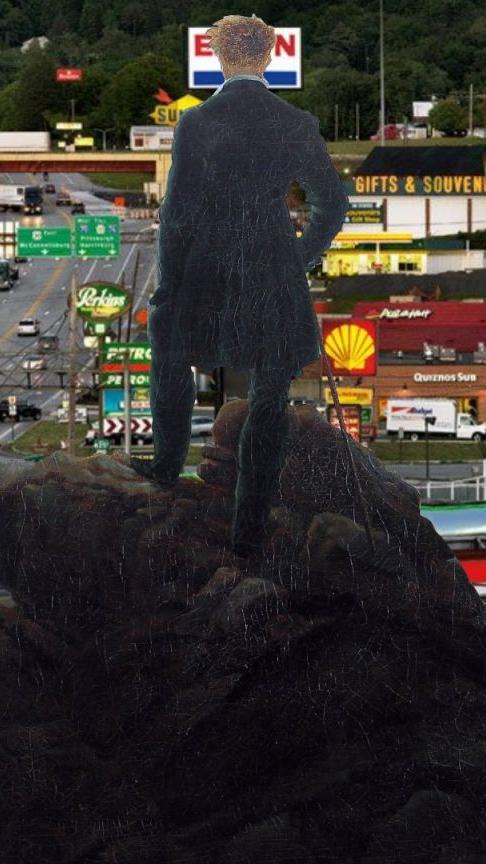

Bruce Davidson, Circus, 1958 © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

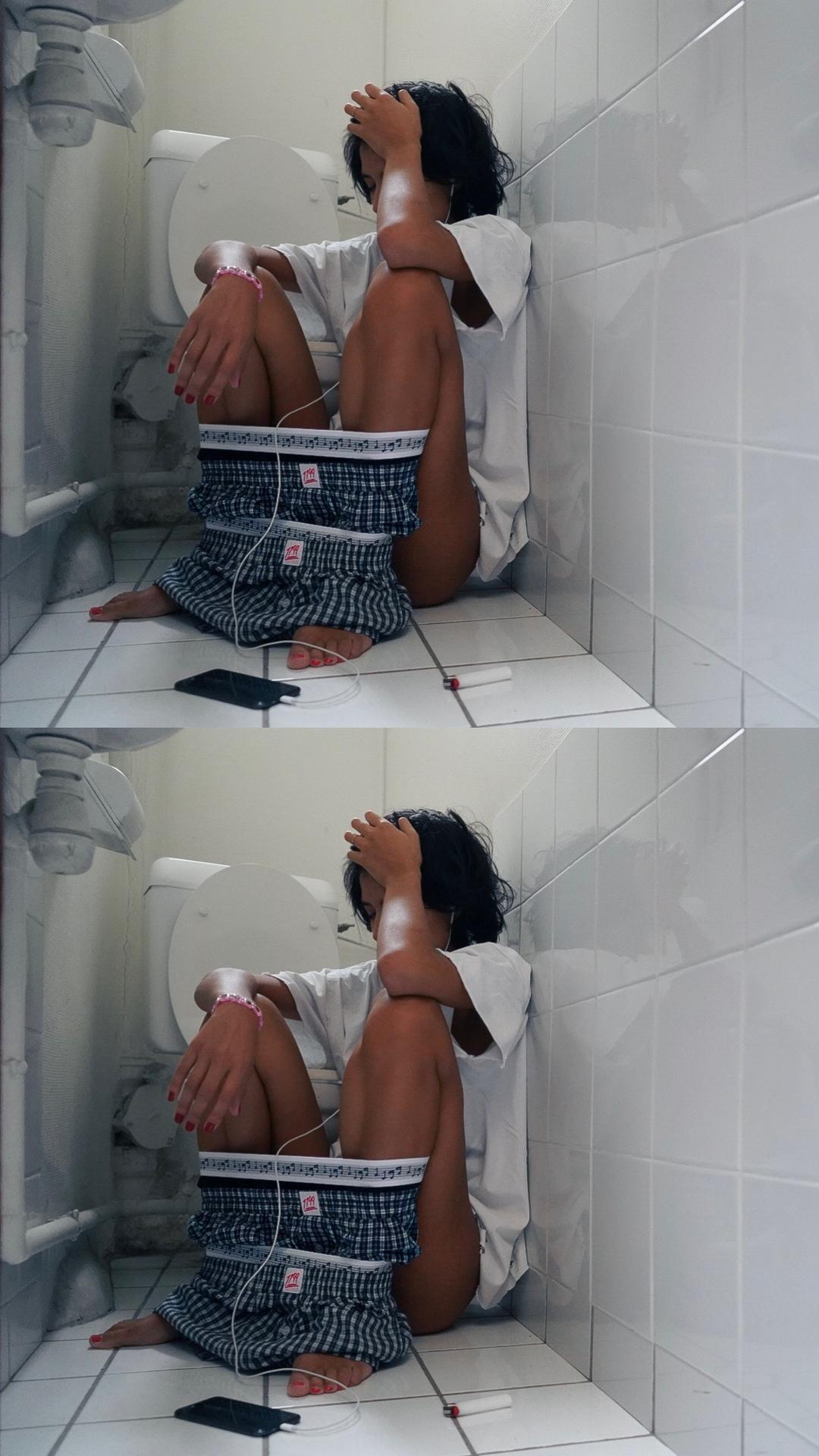

Whatever the case, the final installment of ‘Circus,’ captured nearly a decade after the first, depicts a mode of entertainment in decline. A one-ring tent in Ireland, photographed almost as an afterthought on Davidson’s honeymoon. This installment (or at least what of it was published in his Circus hardcover) features some of his most performance-focused images: contorted bodies in improbable positions, leaping horses, things on fire. It feels like a parting homage, one last celebration of the physical feats of performance before a changing world ended the show.