Notes On Muses

The spark can come from anywhere. O’Keeffe went out to New Mexico looking. Bukowski found it in the fifth drink. Monet walked to the pond.

Creative impetus is magic, and it is rare. Sometimes it comes from another person. These people are important. We call them Muses, and the work of many artists run on them. The artists think so, at least.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/49eed426796eeba898ad1cf8e80e8b41e1303618-1201x842.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=601)

Minerva and the Muses, by Jacques Stella

In Greek Mythology the muses were a group of goddesses (standardized at nine in the classical period) who were thought to contain the knowledge of, and inspiration for, different creative disciplines: Calliope for poetry, Terpsichore for dance, and so on. Artists would pray to muses for inspiration, sometimes even spend the first few sentences of a work on an homage to them.

Marianne Faithfull / Getty Images

In our age, the concept has descended from unseen divinity and landed in people. Beautiful women, mostly. But that is not to say that what they represent is any less mystical now than it was then. Muses exemplify the magic contained in individuals. It is an open question whether this is a supernatural force or a matter of projection. One shouldn’t look a gift horse in the mouth, after all.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/2a48d9de32156b4ec8b83ffe6c165c07691cc4cb-930x615.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=465)

Lydia and Matisse by Henri Cartier-Bresson

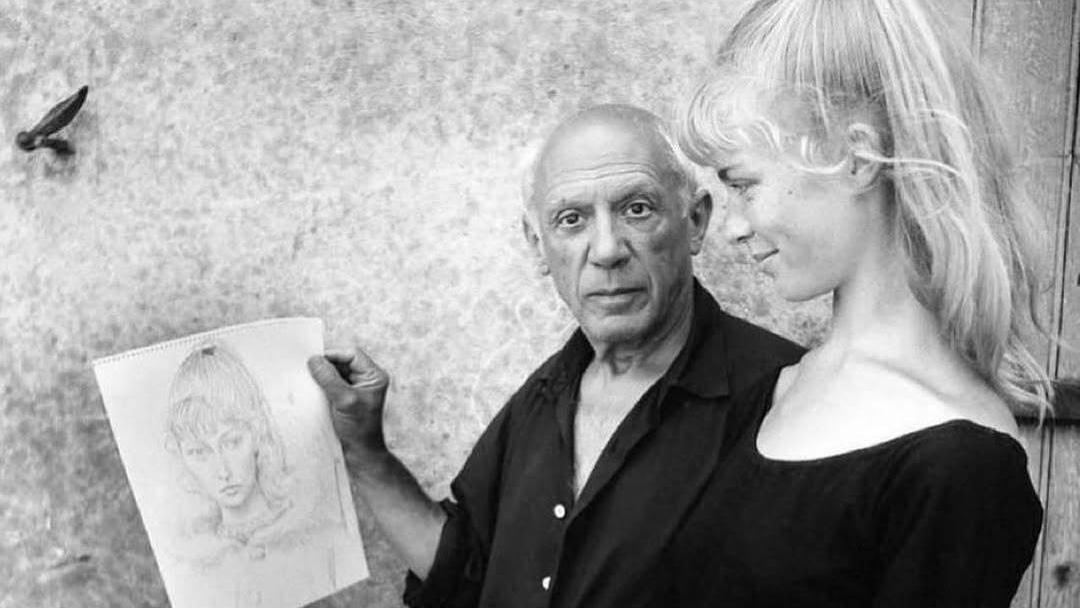

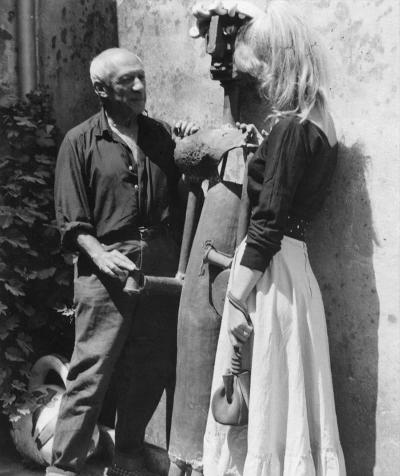

Whatever their exact nature, it is undeniable that muses have been a part of many important works of art. Lydia Delectorskaya was the muse behind Henri Matisse’s “Woman in a Purple Coat.” Picasso’s string of muses includes Dora Marr (Weeping Woman, Portrait of Dora Marr, and Woman Dressing Her Hair), Sylvette David (the 19 year old inspired one of his most concentrated bodies of portraiture), and Marie-Thérèse Walter (a favorite model during his surrealist period). “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” and “Wild Horses” were both written about Marianne Faithfull. Ana Karina’s creative and romantic partnership with Godard delivered a handful of New Wave classics.

Jean-Luc Godard and Anna Karina, 1961 SAUER Jean-Claude

Sometimes a muse can captivate with one physical characteristic. Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal’s hair, for instance, captivated an entire movement. Siddal and her red mane are central in several famous Pre-Raphaelite compositions. The group's conception of ideal female beauty was a core to their aesthetic; Siddal, in turn, was core to this conception. She has been referred to as the first supermodel.

Regina Cordium, Rossetti's 1860 marriage portrait of Siddal

A lock of Siddal's hair

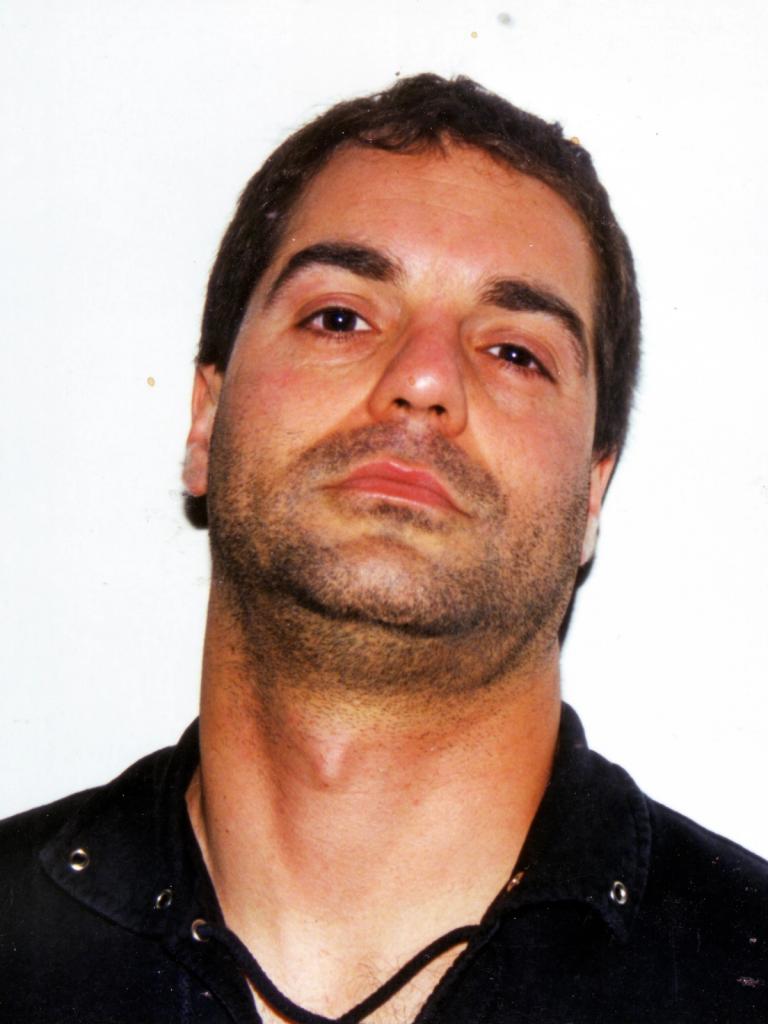

Sometimes a muse’s persona generates their allure. Jacques de Bascher was a steward for Air France when Karl Lagerfield met him in 1971. He didn’t stay one for long, and adopted a vocation of partying and rakish behavior for the remainder of his life, which ended prematurely in 1989 as a result of AIDS with Largerifled at his cotside. In the years intervening, de Bascher developed the reputation of a menace in the Paris fashion scene, carried on an affair with Yves Saint Laurent, and threw an infamous orgy partially funded by Largerfield. De Bascher’s magnetic personality and style served as a significant source of inspiration for Lagerfield, and in the years of their connection the designer found international acclaim and saved Chanel.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/ba4ef0fa9ea8358d17173498a6c44fae9a5d3d28-1487x1999.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=744)

Jacques de Bascher

A conspicuous portion of the time, a muse’s story ends tragically. Siddal, for instance, died at 32 of an opiate overdose.

Triptych, May–June 1973, Francis Bacon, 1973.

Another tragic tale: painter Francis Bacon met muse George Dyer in a bar in 1963, and for the duration of their relationship a drink was never far from hand. Dyer was charming, criminally inclined, and quick to trust. Bacon was famous and incredibly talented, and painted Dyer repeatedly (Three Portraits for George Dyer, Portrait of George Dyer Talking). It was a tumultuous relationship, violent periodically. Over time, Dyer began to feel neglected by his companion. Eight years after they met, two days before a major Bacon opening in Paris, Dyer killed himself. Bacon’s The Black Triptychs were created in the wake of this loss.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/089a42f0a3cf46c928d8af84c88fe5af3ffe1cdb-1127x1200.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=564)

George Dyer in Francis Bacon’s studio, John Deakin, 1965, Source: Sotheby’s

Edie Sedgwick is another tragic muse. After inheriting 80 racks from a grandparent and moving to New York, Sedgwick met and captivated Andy Warhol at a party. She rode the Warhol wave, was dubbed one of his ‘Superstars’, and became an It-Girl (when that term still meant something). After falling out with Warhol, Sedgwick obtained secondary museship with Bob Dylan. The songs ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ and ‘Just Like a Woman’ are rumored to be written about her. Dylan spurned her too, eventually.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/fdc0140e4e176e313b65a0bc1db3f10b10bab75f-1045x1440.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=523)

THE MOD COUPLE Sedgwick with Warhol in 1965. Photograph by David McCabe.

What Sedwick really wanted, though, was a successful acting career. This she could not have. After one audition Norman Mailer admitted she was talented, but said “she used so much of herself with every line that we knew she’d be immolated after three performances.” The performances never had the chance. Sedgwick’s drug use deteriorated with her social standing. At 28, she died in her sleep of an accidental overdose.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/2868963f76e3a5ac77ba0eca6052d61d9280c92d-1266x2000.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=633)

Sedgwick photographed by Bert Stern. © The Bert Stern Trust.

Stories like these underlie a troubling aspect of the muse, namely whether there is something exploitative about these relationships. Muses are cherished and celebrated by those they inspire, but it is a cherishing which, in the end, has nothing to do with them as people. Muses, to their artists, are tools. It can be a transactional relationship which leaves many muses abandoned when they cease to spark creativity. It is no coincidence that the throughline of the experiences of Sedgwick, Siddal, and Dyer are feelings of neglect and loneliness.

Today, it feels like everyone we know is vying for museship, attempting to make idols of their digital avatars. Now, of course, this is less directed at individual artists, more at the anonymous mass of online spectators. (Say what you will about Levinson’s “The Idol,” but it is an excellent investigation of this sort of fragmented narcissism - every character in that show is an ‘idol,’ but only to themselves. I digress.)

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/d7e5dac5533243809a7f299885a431174b5e4536-1200x796.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=600)

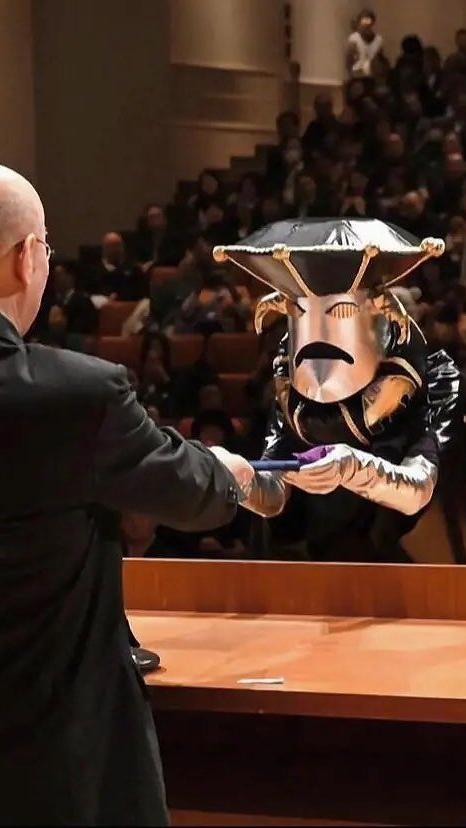

Lily-Rose Depp and The Weekend in The Idol.

This is not to say that artists should not look for muses. Identifying enchantment is probably more important now than it has ever been. But those who seek to do the enchanting, rather than be enchanted, should be wary. As the muses of history show, to be an inspiration is not necessarily to be loved.

A sketch of Sylvette David

Image curation by Carly Mills