What Is Performance Art?

As an idiom, “needle in a haystack” works because its implication is ambiguous. It sounds impossible, tedious to the point of absurdity. Of course, if your life depended on it…

Sven Sachsalber at work (© Reuters)

Sven Sachsalber’s life did not depend on locating a needle in a haystack, but his 2014 performance at Palais de Tokyo in Paris did. Which begs questions about the value of such performance. A man sifting through a pile of hay in search of a needle the gallery director hid there--does anyone actually care? Artnet and Time and Hypebeast all wrote five-ish sentence pieces on it, so maybe?

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/d1d039193678a64fd71cd0105e469bc521c20026-1240x752.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=620)

(© Reuters)

Performance art (like, for the record, all art) exists on a spectrum between transcendent and stupid. It’s one of the more controversial disciplines in this regard, not just in comment sections but in audience discussion everywhere. It is a common joke to refer to something esoteric or pointless as performance art. Meanwhile, very earnest artists continue to produce, often to great acclaim and financial gain.

At its most basic level, performance art refers to any artwork or exhibition that requires live action for its execution. This live action can involve both artist and audience. It can occur in a conventional artworld space, on the street, or anywhere else. As a term, it arose in the 1970s and denotes an array of subfields such as body art, endurance art, happenings, process art, and guerilla theater.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/f14dc28cf12c174b328520f43fea55ccff076091-1074x1269.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=537)

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917

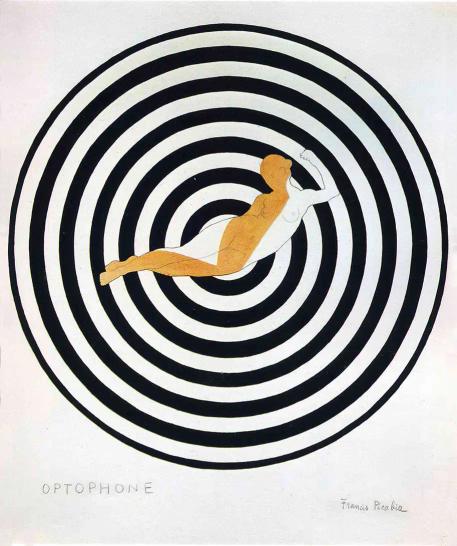

It is perhaps telling that performance art emerged out of an artistic movement explicitly committed to not making any sense; some of the earliest instances of performance art come from early twentieth century Dadaists. In large part a response to the paradigm shifting destruction of WWI, Dadaism rejected logic and reason in favor of nonsense and irrationality. The dynamic and impermanent movement of performance art is perfect for this sort of thing. If you think that being static or interpretable are shortcomings of conventional art, then eschewing images or objects in favor of movement and action is a logical step.

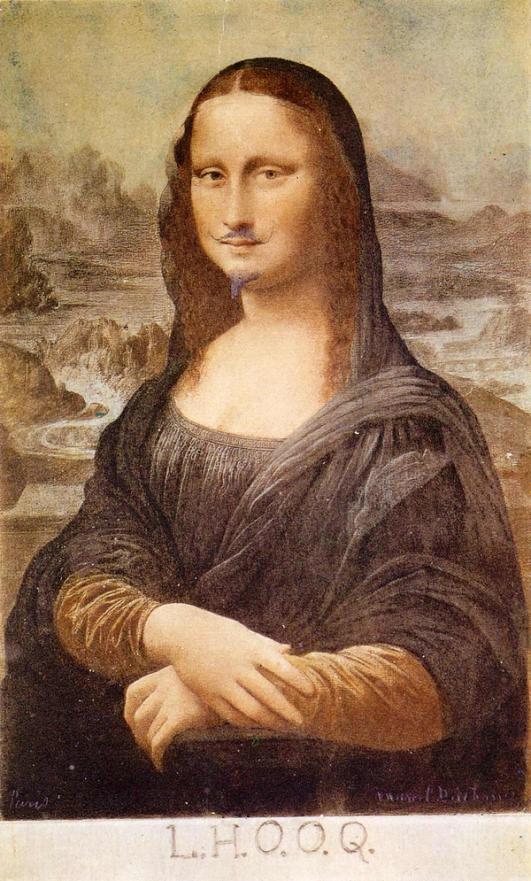

Several key works from the Dada movement: Optophone I by Francis Picabia, 1922. (Source: wikiart); L.H.O.O.Q. by Marcel Duchamp, 1919. (Source: Staatliches Museum Schwerin); The Mechanical Head (The Spirit of Our Time) by Raoul Hausmann, 1920. (Source: Centre Georges Pompidou)

This also makes performance art harder to evaluate. Of course, evaluation is not the point of art. In many cases, impenetrability is a strength. But an easy critique of performance art is that by priming viewers to receive something with aesthetic meaning, performance art preempts both meaning and aesthetic. In other words, performance art can fool viewers into thinking something silly is profound artistic creation. Someone screams at a gallery wall while well-dressed and half-drunk onlookers nod along: we’ve all been there.

There are those people who simply need to be told something is art to fawn over it. Performance art preys on these people precisely because it is so nebulous. It is said to ‘explore themes of’ X, or ‘interrogate’ Y, and simply by virtue of this declaration convinces much of its audience that it does so. When this is true, performance art falls into the same traps it originally aimed to overcome.

But to reduce all performance art to the level of its worst instantiations is as much of a failure as the reverse.

Many of the most famous instances of performance art approach social experiment. Take “Rhythm 0,” a 1974 work by the preeminent performance and conceptual artist Marina Abramović. A simple concept: for six hours the artist would allow an audience to do to her whatever it pleased. There were 72 objects in the room, including a gun and a bullet.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/34ade04c20196856afeaf699685a892d0d3a808c-880x1326.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=440)

Instructions for Rhythm 0, 1974 (Photo by Tiroche DeLeon Collection & Art Vantage PCC Limited)

A first tame hour was followed by five harrowing ones. Abramović’s clothes were cut from her body, she was groped and assaulted, her throat was slashed, her blood sucked. At one point the gun was loaded and held to her head, at which point a fight ensued (Abramovic remained still and resistanceless all the while) and the gun was never fired. When the six hours were up, the audience fled.

Images from the performance of Rhythm 0

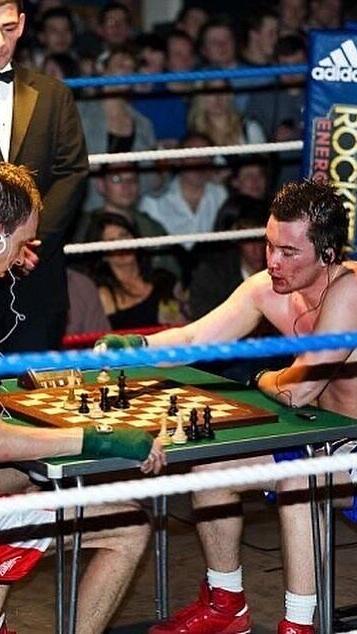

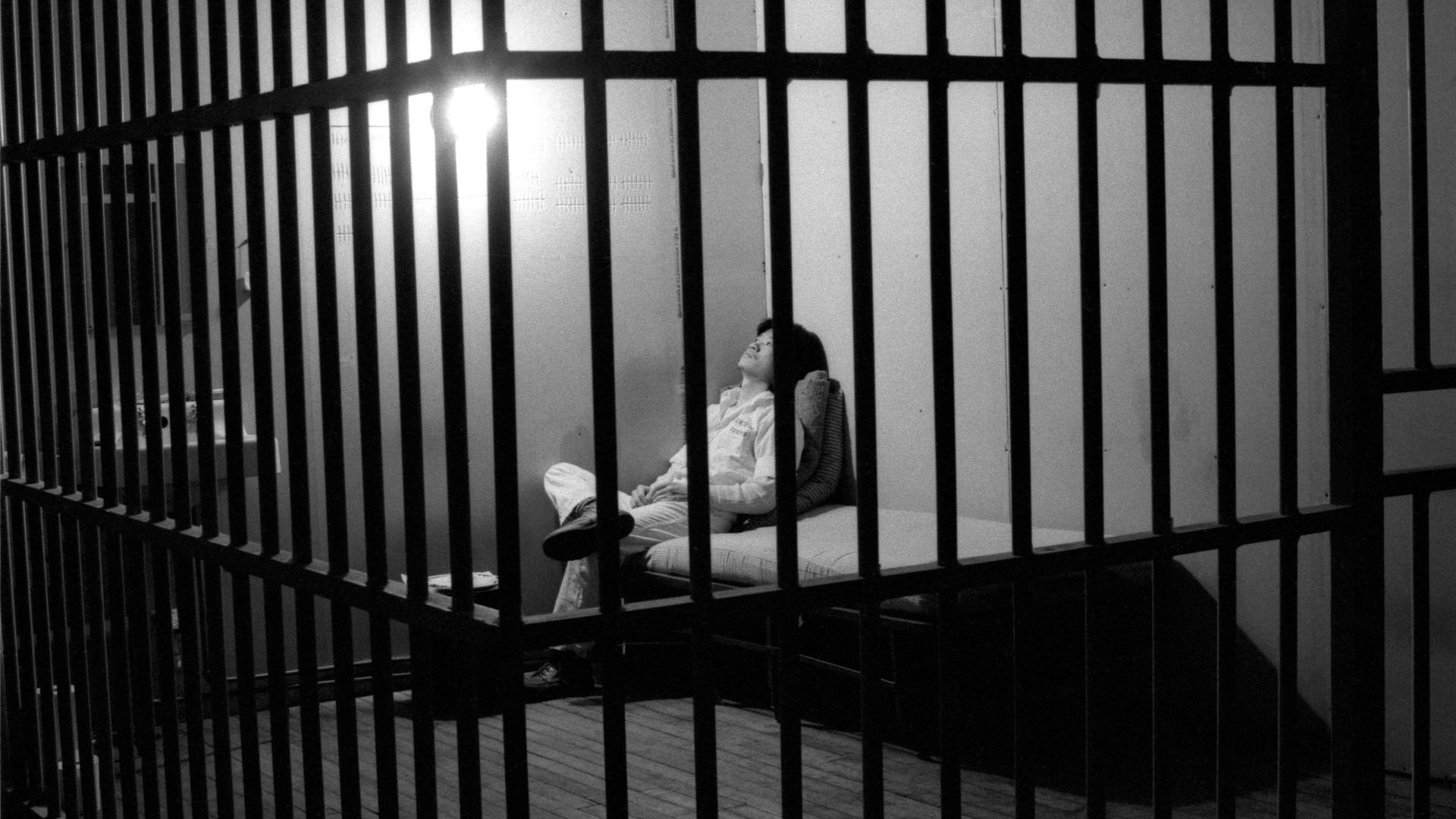

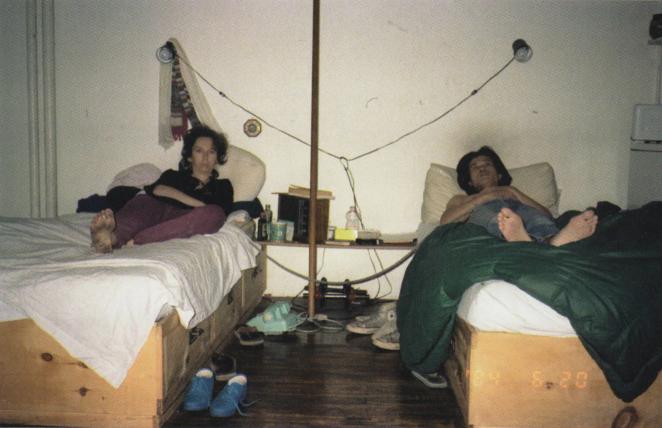

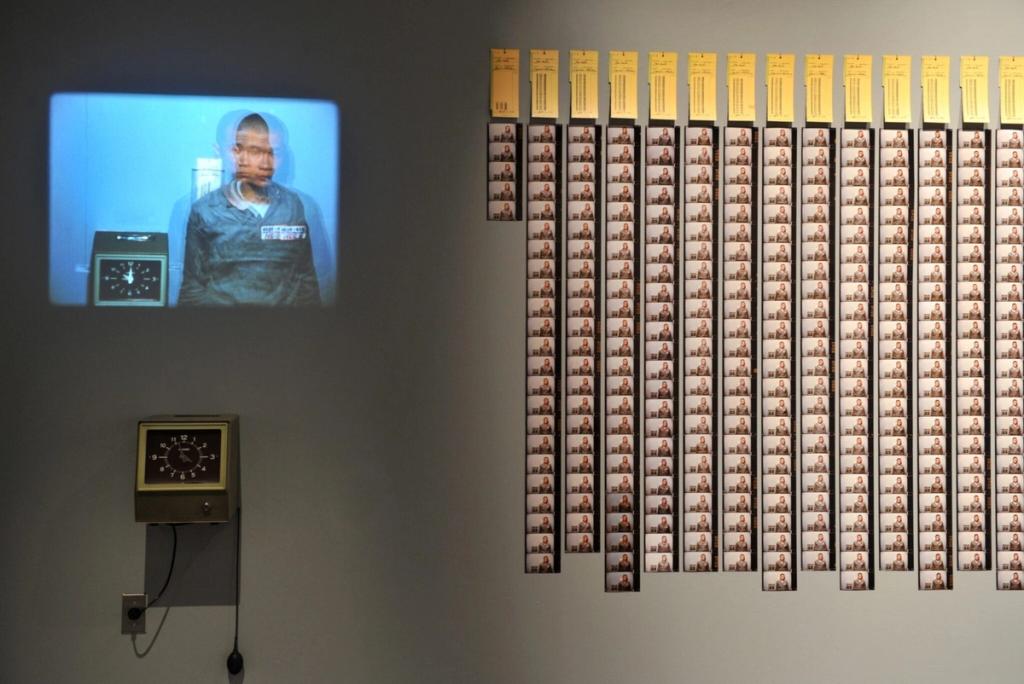

If Rhythm 0 investigates what an audience is capable of, Tehching Hsieh’s Cage Piece investigates what an artist is. Hsieh spent a year in a cage. This was part of a series of five works collectively referred to as his “One Year Performances,” which spanned from 1978 to 1986.

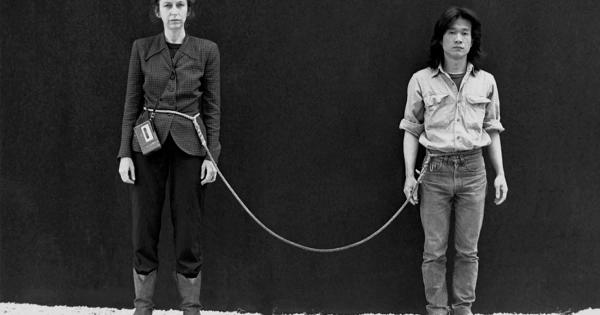

In addition to spending a year locked in a cage, Hsieh spent a year punching a time clock every hour, a year entirely outdoors, a year tied to another person, and a year completely avoiding anything to do with art or the artworld.

Tehching Hsieh, Art/Life One Year Performance 1983-1984, New York. © 1984 Tehching Hsieh, Linda Montano. Courtesy of the artists and Sean Kelly, New York.; "Punching the Time Clock." Photo by Michael Shen. © 1981 Tehching Hsieh. Courtesy of the artist and Sean Kelly, New York.

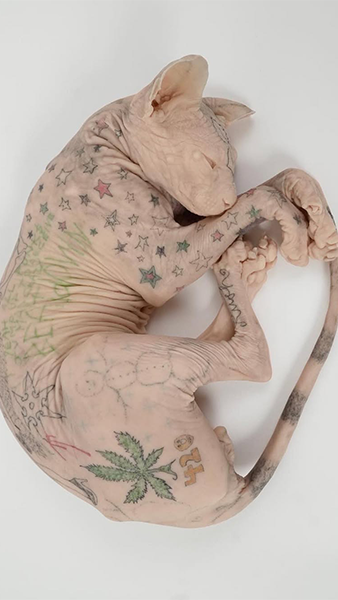

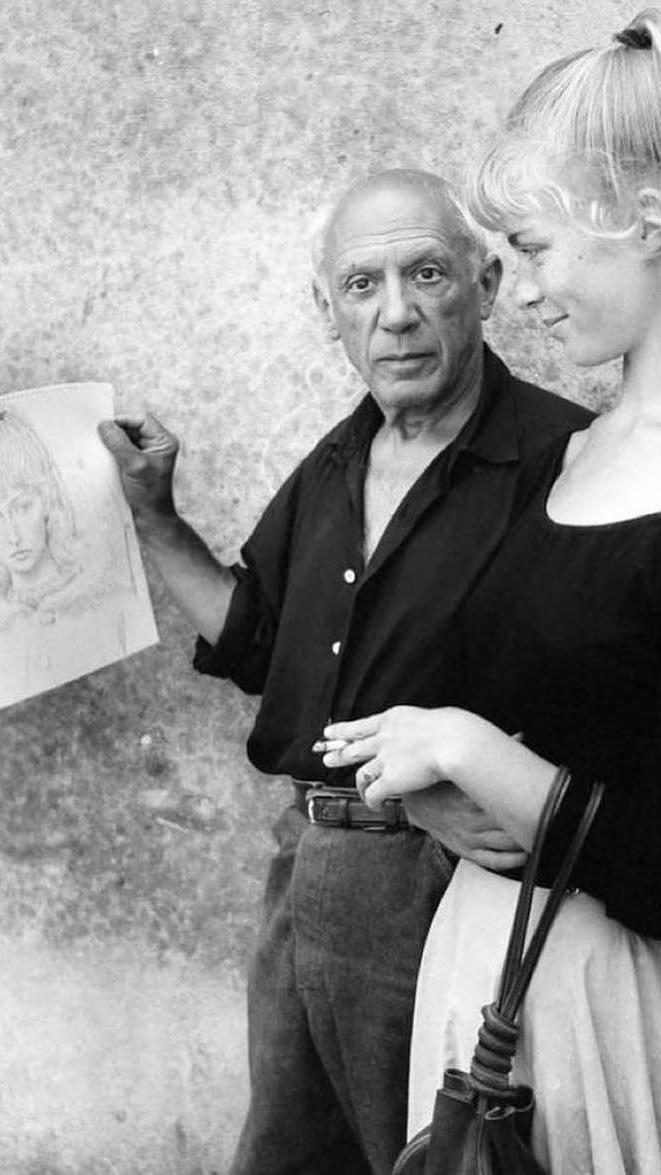

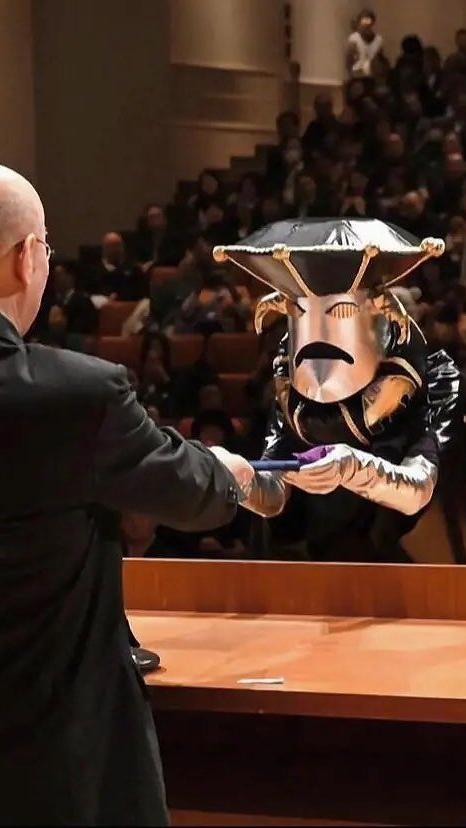

Joseph Beuys’s work, such as How to Explain Picture To a Dead Hare and I Like America and America Likes Me, exemplifies performance art utilizing absurdity. In the former, performed in 1965, Beuys spent three hours strolling through a gallery with a dead rabbit swaddled in his arms, explaining the displayed art into its unhearing ear. In I Like America Beuys wrapped himself in felt and lived in a SoHo loft with a live Coyote for several days. People were compelled by these. Before you write them off, check them out. You might be too.

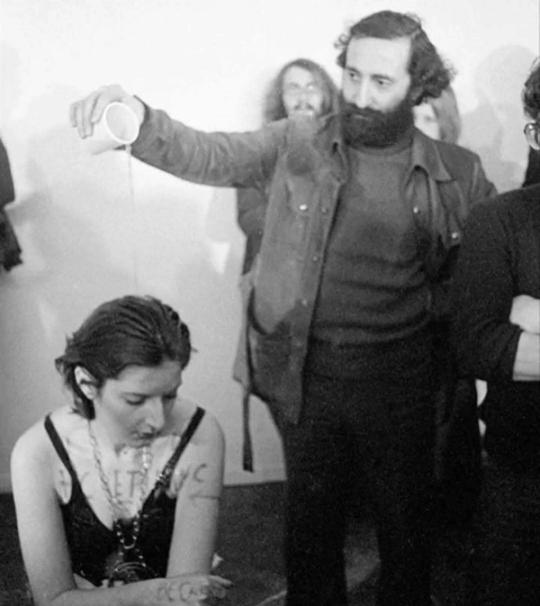

Beuys during his Action How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare (Wie man dem toten Hasen die Bilder erklärt), Schelma Gallery, Dusseldorf, 26 November 1965; and in I Like America and America Likes Me, 1974.

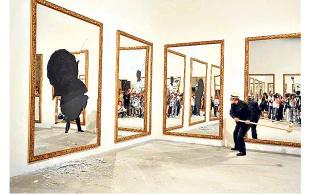

But not all performance art is experiment or absurdist composition. Performance art is also a vehicle to create and recreate a single moment in all of its immediacy, without relying on any sort of documentation. Michelangelo Pistoletto’s work featuring the destruction of mirrors is like this. In “Seventeen Less One” and Twenty Two Less Two Pistoletto destroys mirrors in gilded frames in front of excited audiences.

At the opening ceremony of the Venice Biennale in 2009 Pistoletto presented the action and installation Twenty-Two Less Two

Other performance artists have utilized the medium of human action for political ends, such as Teresa Margollis, who for the 2009 Venice Biennial cleaned the floor of the Palazzo Rota-Ivancich exhibition space with a mixture of water and blood from Mexican murder victims.

Teresa Margolles. Cleansing, 2009. Cleaning of the floor of the exhibition halls made with a mixture of water and blood of people murdered in Mexico. The action took place repeatedely during the Venice Biennial.

Whether you find all of the foregoing compelling or asinine, they should at least illustrate a few possibilities for value in this kind of art. It can be an arena to push human capability to its limits. It can be a theater for absurd situations and commentaries. It can utilize human action to reproduce a dynamic moment without any documentation as intermediary. It can speak to contemporary issues better than a mural.

It can also just be sort of interesting. Let's return to Sven Sachsalber’s piece. Wasn’t there a part of us that had been curious about that idiom, that wondered at the seeming impossibility of finding a needle in a haystack? Isn’t it sort of delightful that somebody actually tried–and succeeded? Even his strategy was interesting: take a handful of hay, not too large, fold it a couple times and bend, and, theoretically, if the needle was in that handful, he’d feel it. He did, after 18 hours.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/44ca0d266f8367e4d07b75fa499b340c7b511318-1080x1080.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=540)

(© Reuters)

The sad truth is that in our day vigilance is required. There is a lot of bad art, plenty of bad artists peddling it, and money to be made doing so. As art, its making, and its consumption have all increasingly become attributes of personality, rather than crafts, pastimes, or obsessions, impure motives are rampant.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/220f8cc62c6480792275d32c2af2dc9098a990ee-2560x1814.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=1280)

I Like America And America Likes Me, 1974. Photo from Collection SFMOMA

But although performance art is susceptible to this trend, we should not lose sight of the fact that, at its foundation, it is nothing more or less than the broadening of artistic expression’s possibility via the introduction of action and movement.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/e4026e4319ac68c04f738928f283af51a1661b1d-1240x698.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=620)

Tehching Hsieh, Art/Life One Year Performance 1983-1984, New York. © 1984 Tehching Hsieh

The difficulty, as always, lies in being judicious. Here again we are returned to the value of taste. Hard to teach, indispensable to have. There is no rubric, no one right way. But without it, we are doomed to accept someone else’s definition of quality art. Which can lead you into galleries where people scream at the walls. Beware.

Image Curation by Erild Kondi (@kondierild)