The Return to Early Virtual Aesthetics

For at least the last three decades, hyperrealism has been a central goal of virtual visual development. Sharper resolution on screens yes, but also improved texture quality and anisotropic filtering for our games, anti-aliasing and higher frame rates for our cameras, more immersive home entertainment systems, a system of judging virtual images by representational fidelity.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/a8aa57dcfa6c9d6dc011415fa9df84257000a024-450x337.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=225)

Dan Hays, Colorado Snow Effect 4, via @danhayspurple

While we haven't achieved perfect realism, the precision and accuracy of virtual imagery has reached a point of legitimate imitation–there are fervent debates about whether certain images are ‘real’ or AI, pixel counts that far exceed the naked eye’s optical ability, and VR games that make people think they’re falling to their death from a living room carpet.

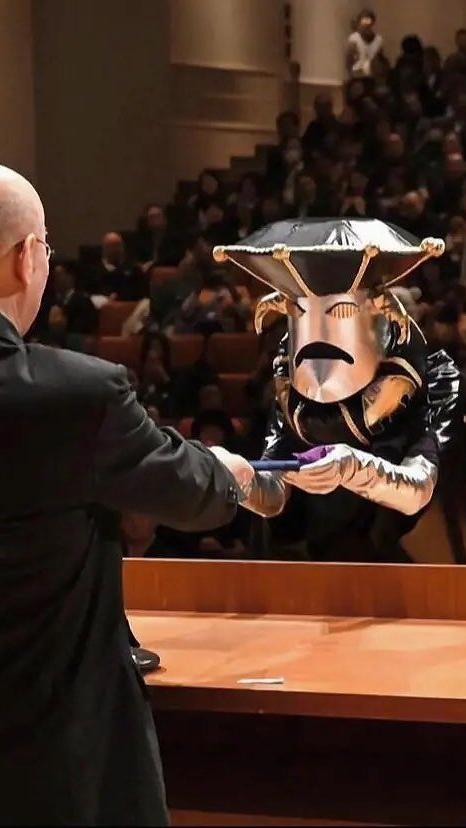

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/6b01036eba9a8935ee428a08d5439c715ac7ccff-640x776.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=320)

Recent Doechii ads for Denial Is A River are an explicit homage to The Sims 2 advertisements

You could argue about whether any of this is a normative good. What’s a positive fact is that great effort and money were expended to get us here. The spenders of these might be concerned by the fact that, as we approach the virtual hyperreal, people don’t seem to want it.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/9245f847ea2a3974d952a26b3ca0c5c36c481214-3800x2414.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=1900)

Faig Ahmed, Tradition in Pixel, 2010. Photograph: Faig Ahmed

The growing fetishization of early virtual aesthetics is one signal. It comes in many forms: pixels on the runway, fine artists painting bad graphics, people using filters to look like GTA III characters, content creators bordering photos in ancient IOS interfaces, a general obsession with the analog and nostalgic yearnings for bygone ways.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/2bee43c4f43d010f8cb390ffbecd43edc0d56e51-1024x1758.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=512)

Gao Hang, Not on my motherf**king watch!, 2021.

It’s easy to say there’s nothing unique about this rejection–exhaustion is a normal response to any dominant aesthetic. But the return to Early Virtual aesthetics is different from cyclical obsolescence. The hyperreal is more than a style or a trend–it is a technological paradigm founded on an assumption about what people want out of images. What if the assumption is wrong?

–

Some examples.

For their SS 23 show, Loewe designed several garments to appear in 8-bit render, pant-patterns to mimic pixelating tones, and jackets to sit in front of the body like a bad skin. They’re far from the first but embody a mature incorporation of the Early Virtual into fashion: in most cases the pixel merely becomes a fabric pattern, but Loewe’s garments were formally digital.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/8e2d1ad3bbf0e91857a18bbb668ae50d49437ba7-980x1470.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=490)

Loewe Early Virtual SS23 look. Photo by Isidore Montag

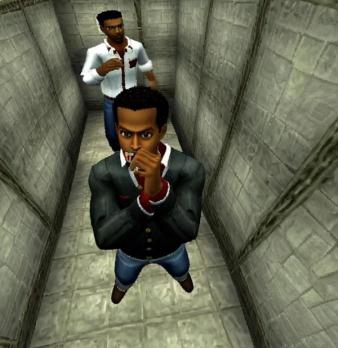

Fine art is a more commodious medium for the Early Virtual. Gao Hang primarily works with acrylic on canvas and depicts some of the most egregious mis-renderings of Early Virtual graphics. These idiosyncrasies, once regarded as mistakes, are made central in Gao’s compositions. E.g. the warped layering of two faces coming together, the sudden transparency of an object that gets too close to POV, the odd geometries of limbs and hairlines.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/5156a0aeee5ed2612148665bf37155533ddf4335-2880x2833.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=1440)

Gao Hang, A Stranger To The Internet (Copyright © Gao Hang, 2024).

Sasha Yazov is another artist taking up Early Virtual subject matter. Yazov’s work is less ostentatious about the specific shortcomings of digital images and seems more interested in their claim to beauty. His description of practice is also more explicitly nostalgic: “taking us back to a period when…the internet still seemed a platform of freedom and unprecedented opportunity for everyone.”

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/837ac48f8d9029aeaadd5fa55833c832de3b97f3-2385x1776.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=1193)

Sasha Yazov, Untitled.

Maja Djordjevic’s work examines specific icons of the Early Virtual. Interfaces of archaic paint softwares are one example. Djordjevic’s canvases look like the modems in a 2007 school computer lab after an hour of free time. In fact, they are oil and enamel, and composed without the assistance of tape, stencil, or projection. Here, the digital aesthetic is rendered completely organically. The human hand imitates the obsolete machine.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/f7bde2d305b510886ef27ec62662f196c49241b9-1167x1600.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=584)

Maja Djordjevic, Love Your Way

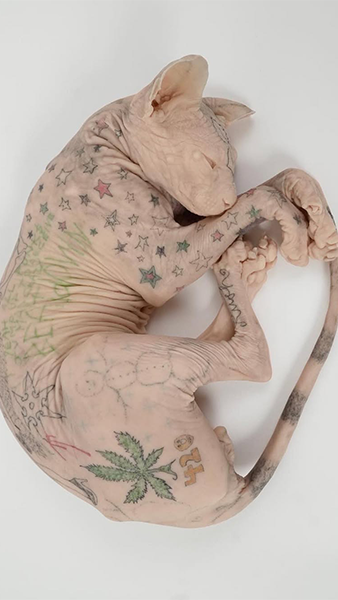

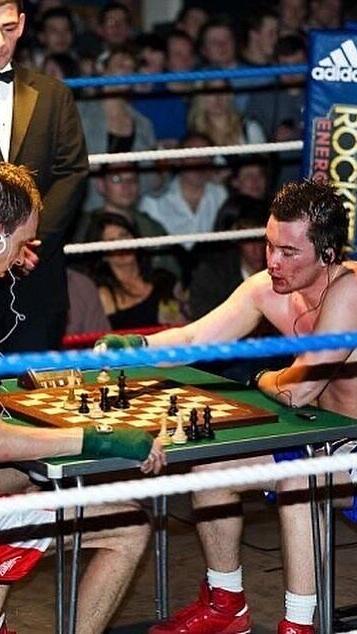

Digital art is a distinct case. Rather than filtering the Early Virtual through their own medium and materials, these artists return to the digital itself for their renders. Artists like Victor Estrella, Bully Dee, and Sluj convey the aesthetic virtually in an interesting down-filtering process where screens are asked to convey images at a fraction of their capacity.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/0368c4704a5ec4d391764a3151fc8a4a72b8a6d2-940x708.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=470)

An image by Victor Estrella, via @vicestrella.psd

Others don’t commit entirely to the Early Virtual, and instead incorporate only certain components into a larger composition. Jack McVeigh practices this blended approach. The role of low-poly in his work is selective rather than immersive.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/b44229b4d956707bcd0d9133b785f030b482e22f-600x1067.png?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=300)

9-5 Grind, Jack McVeigh, 2023

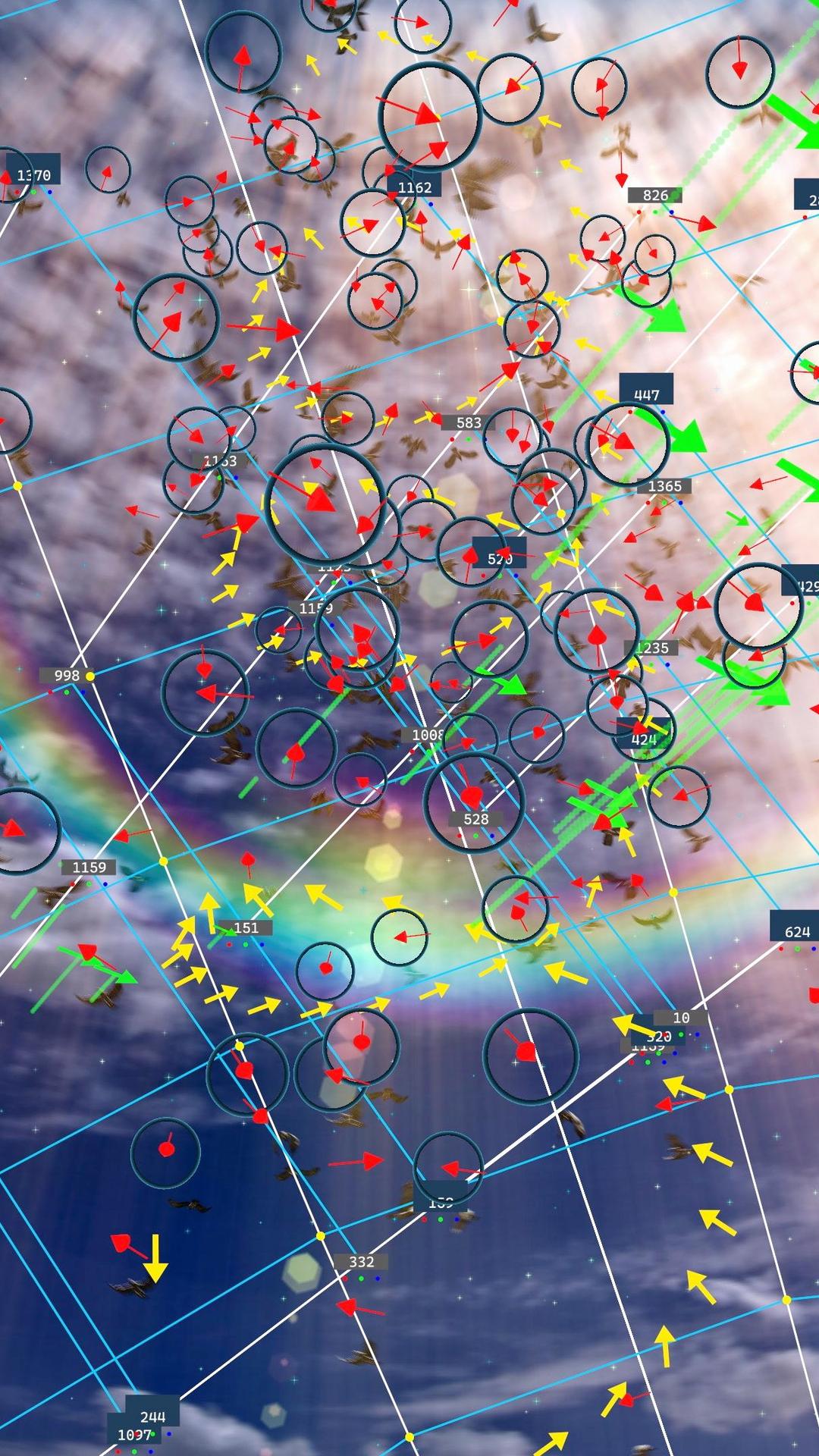

Jon Rafman’s incorporation of Early Virtual inadequacies bear making another marginal distinction. In Rafman’s work the Early Virtual contributes to an atmosphere of just-wrongness, a focused and intentional use that feels like a more developed incorporation of the Early Virtual into the artist's toolbox, a glimpse of a future where it is a style instead of a reference.

There are also archival projects like Haunted PS1 that have found success in preserving and recreating these aesthetics for a specific interest group for years.

But art is not the frontier of this trend. Many of the referenced pieces are more than five years old. The expansion of Early Virtual aesthetics today is most rapid on personal accounts, among digital avatars. Increasingly, users are ornamenting their virtual selves with the Early Virtual. Images captured on noncurrent digital devices, the re-rise of old-gen iPhone photography, low quality as status symbol. More explicit efforts like the de-rendering technique of feeding images through an AI mechanism to return Playstation 1 level low-poly versions, and subtle nods like the presence of a photo-app border from an older IOS. The list goes on.

TikTok user @hurtabdu1 posted the earliest viral slideshow featuring images of him in a PS2-styled filterulign

Each of these mediums’ (fashion, art, personal content) incorporation of the Early Virtual is distinct. Loewe desired a striking silhouette that would resonate and sell garments; artists’ fascination with the Early Virtual’s formal qualities is dissimilar from digital point and shoots on personal feeds, which probably have a lot in common with the normal reasons people post things on social media–self-differentiation, status signalling, a counterprogramming an oversaturated status quo. Each usage warrants separate analysis.

—

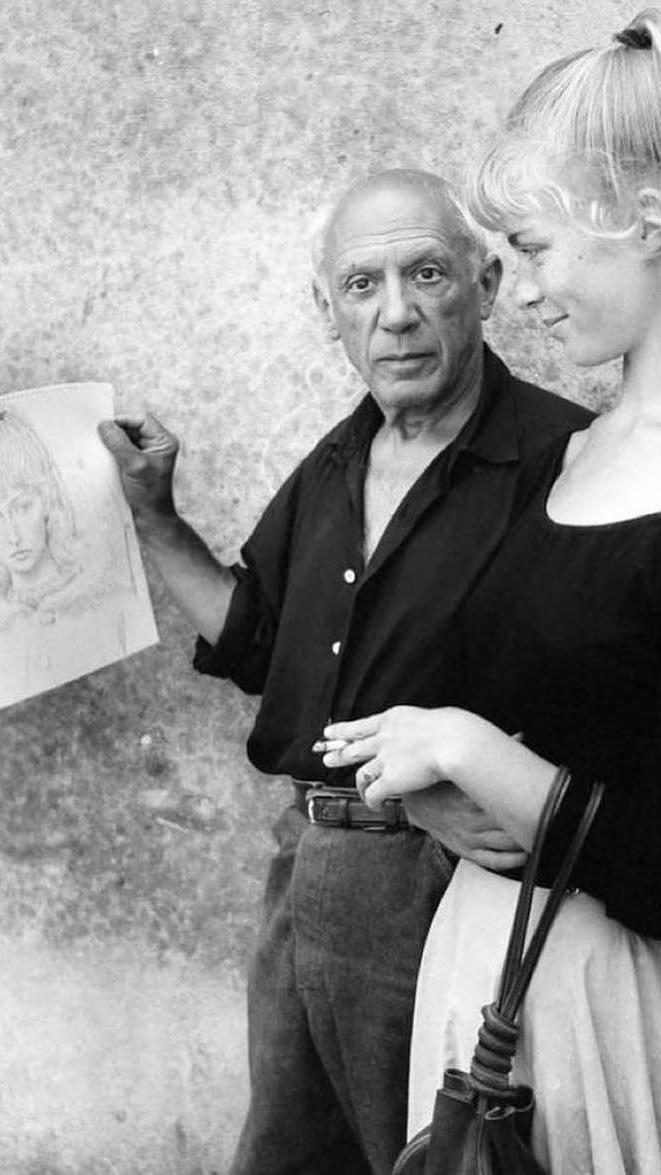

Technological inadequacies come to define their eras. Brian Eno said it in 1996: “Whatever you now find weird, ugly, uncomfortable and nasty about a new medium will surely become its signature.”

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/96f0ef356d35ab180f7daeb3f44d89c94d908279-1000x600.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=500)

Brian Eno by Erica Echenberg/Redferns

Part of the answer to why is nostalgia. It’s a powerful feeling. Every moment of childhood videogaming bliss returns in a compressed instant when I see screenwarped Lego Jar Jar Binks. In our contemporary context, increased accessibility to the archive means that seeing the past has never been easier, only enhancing nostalgia’s grip.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/18ac344ba60a4cc91de490056546054fe7fb9774-1080x1080.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=540)

By Sasha Yazov via @sashayazov

But the question isn’t just Why does this aesthetic move us? but: Why does it move us more than ‘superior’ virtual aesthetics? Early Virtual imagery is, by every observable indication, instantiating aesthetic experiences that are outcompeting technically worthier images.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/1382719b7863b54e6749cbc71012e03c31e7e001-1600x1200.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=800)

Jon Rafman, You Are Standing in an Open Field (Waterfall), 2015

This has as much to do with the state of the contemporary image as it does Early Virtual ones. The image is in crisis. It has never been harder for an image to mean anything. They don’t compel us. They did once, many of us remember. When they did, they looked like this. We don’t want perfectly immersive graphics. We want graphics that make us feel the way we felt playing Pokémon Red.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/0a840c456e6fa503a9c5f06005290e89d6c053cc-1108x997.png?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=554)

Still from Pokemon Red / Blue (Game Boy, 1998).

A limp contemporary image meeting a groundswell of nostalgia together paints a compelling picture. But the return to Early Virtual aesthetics begs another question about the way we define ‘superior’ and ‘inferior’ images.

The frantic pursuit of image quality was the result of a marketing arms race in industries whose goal is to sell us screens. Their assumption has been that higher quality and greater realism are inherent Goods is one that has its origins in markets, not aesthetics.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/8774814a03c5c7d161afee74d94c4ea66e9e5bd6-1920x1955.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=960)

Gao Hang, I am so pro-liquify, 2021, (Copyright © Gao Hang, 2024)

The truth is that they don’t know what we want out of images now. Nobody does. Nobody knew what it would be like to have this much visual material in our pockets, exponentially growing, volumes inconceivable. When perfect simulacra isn’t a futuristic promise but a fingertip reality, will we choose it? If the market is an indicator, then the recent struggles of high-budget clean-physics high-res gaming projects are dead canaries. At some point it becomes a math problem.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/dd4cd33da2e014b19d9c1fa0787ed75c31419b45-2400x1500.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=1200)

Still from Jon Rafman's, 'Dream Journal 2016-2017', video linked above. Image via the artist and Sprüth Magers.

There is also immense aesthetic novelty in technological incompetence. Bad tech invents forms. Pixels for instance, or poor video game renders. Wonky, yes, but also new. Virtual interfaces inaugurated an explosion of new forms that we are only now beginning to reckon with. Our screens becoming perfect representations of reality is, in this sense, a mass aesthetic extinction. Perhaps the use of Early Virtual touchpoints today should not be viewed as nostalgic references to an era, but as an incorporation of new forms into our common artistic language.

This is merely brushing the surface.

–

We communicate in images. Prototypically, this would be natural ones–bears on cave walls. Now, we’re beginning to communicate in images the internet invented. We published an article about Yoshi Sodeoka’s art which argued that its depiction of digital senses represents a theoretical innovation. But that same incorporation of forms made by computers is also infiltrating our symbolic language on a larger scale. Much has been said about the ways that modernity makes us behave like machines. Increasingly, we communicate like them too.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/6359cb308905022ec125b3326be81a7a6332c06b-2880x699.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=1440)

Gao Hang, They Like Your Athleticism (Copyright © Gao Hang, 2024)

For most of us though, image to image, the appeal of the Early Virtual is nostalgia. Nostalgia is probably all the descriptive heft one needs for this trend, however branching its implications might be. Alas, we don’t get those days back. Even if we did, they wouldn’t be like we remembered. The past is always gone, perfectly gone, and this remains true even if you can experience its exact representation on an entirely immersive screen.

This isn’t to say that we don’t also want high res TVs, incredible zoom for our phones, truly immersive VR. It's a moot point anyway–we’re going to get it. But access does not imply obligation. The decision remains ours. May we all choose wisely.

Image curation by Carly Mills

Written by Noah Jordan (@nnoahaonn)