Thomas Sauvin’s Beijing Silvermine Project

Thomas Sauvin’s Beijing Silvermine Project begins in an illegal recycling site outside of Beijing. An abject scene: in a room piled high with trash, in a warehouse somewhere in the dump, Sauvin sifts. The trash he is looking through is a curated discard that contains trace or significant amounts of silver nitrate. Such as film negatives. A furtive man who doesn’t like cameras owns the place and employs a team of trash-pickers who scrub the city for this specific trash, which is then soaked in acid-filled sinks for days, weeks. The silver nitrate is then culled and sold, often to be used in laboratory settings.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/b5f83bf0ab18ef27a21fdc4a5daf06fe9bfa731b-500x500.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=250)

Thomas Sauvin: Beijing Silvermine (© Beijing Silvermine)

Sauvin is not involved in the silver nitrate harvest, and his periodic trips save only a fraction of the collected images from this nondescript fate. He does not disagree with the silver nitrate miner that the images are basically mundane. Sauvin’s Beijing Silvermine Project is about the mundane. A history of the masses, told through the photographs they threw away.

© Beijing Silvermine

A particular history. For technical and political reasons, Sauvin’s archive is focused on the period between 1985 and 2005. The front boundary marks the end of the Cultural Revolution and the emergence of a popularly available and operable Kodak camera. On the back end, the rise of digital and the death of film means post-2005 images are rare. In the interim, tremendous change for a country undergoing rapid industrialization, commercialization, and poverty-reduction of a scale the world had never seen.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/3ce64b68911462f0bfb3f81b91cd529c21225971-500x500.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=250)

© Beijing Silvermine

After a brief look through the negatives, Sauvin sends a selection to a man in a small portiere’d apartment on the outskirts of the city who scans, digitizes, and returns. Sauvin then examines more thoroughly. It’s not as antisocial as it may sound. 36 pictures on a roll of film is long enough to get to know the photographer, Sauvin has said.

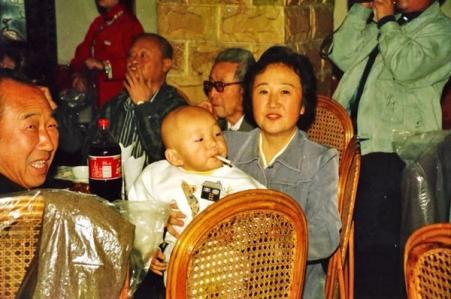

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/8a9c7f25ddce008d1e456c1cc785afc3b2a11977-500x500.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=250)

© Beijing Silvermine

What he does with the images next has ranged widely. For a time he packed boxes with 100 random selections, aiming to recreate the serendipity of his own random discovery. He has also enlisted other artists to work with his trove. One digital artist, for instance, arranged a slideshow/montage that highlights recurring image-types in the archive. This could be the content of the images, such as those of a waterfall in a popular city park, or compositional similarities, like three people on a couch shot five to seven feet away. Sauvin was surprised, initially, by this uniformity. The surprise has worn off. We do, in the end, take mostly the same photographs.

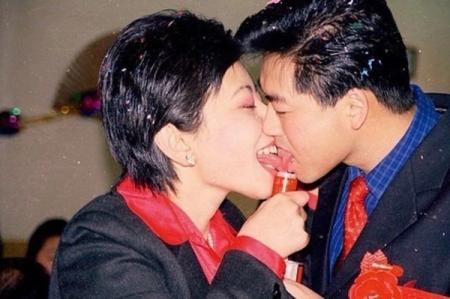

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/b44e031ae47843dcfc6817a528c1cb8721c6f14c-900x598.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=450)

© Beijing Silvermine

Sauvin also likes to organize collections. Some become photobooks, such as the very well known Till Death Do Us Part which spotlights cigarette-related traditions at weddings, many of which seem to involve two-liter bottles with puncture marks for numerous cigarettes to be dragged at once. This particular series leans more alienating, a depiction of a very particular cultural practice. In the series, the western associations with tobacco are subverted. You could argue that this is good or bad (Chinese men consume about 40% of the world’s cigarettes) but for most westerners it is at least entertaining.

But the thrust of Sauvin’s work lies not in the spectacle. The most poignant experience with images reclaimed from the silvermine comes not from the exceptional few, but the recognizable majority. Hands cupping the sun in a perspective warp, family in uninventive arrangement for an image everyone knows is headed for oblivion, consumer goods, tourist attractions, someone stepping into the frame at an inopportune moment and becoming an obtrusive and blurred foreground. Give someone a camera, and these are the images they will make.

© Beijing Silvermine