Lessons On Creative Practice

Creativity is one of the lesser understood human capacities. We don’t know exactly where it comes from, how best to judge it, or even what it is. And yet there are few things we value more in ourselves, our peers, or our species.

Given our nebulous understanding of the essence of creativity, it’s understandable that the specter of ‘Creative Block’ terrifies anyone who relies on being creative for income or self-image. We understand what causes Creative Block about as well as we understand what creativity is. Some think it’s a psychoanalytic failure to channel the subconscious, others that it's the result of neurochemical imbalance or cognitive rigidity. Whatever it is, one knows it when it rears its ugly head, and few escape its clutches forever.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/b29c88d2a0bcecff6c550b36a0a4e63bf049b63d-1024x768.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=512)

Photographer Marco Anelli spent eight years documenting the workspaces of more than 40 famed artists for his book Artists Studios New York / Dana Schutz's New York studio, 2012. © Marco Anelli.

To combat the whimsical and capricious beast we have: routine. A standardized way to go about creative practices that offers some sense of structure to the structureless, that attempts to form out of fog something consistent enough to found a career on.

Everyone’s is different, but here are a few principals pulled from a few greats.

Unlock the subconscious

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/96e13295a798edd2434d73a92796dab1129f1c1b-2000x1496.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=1000)

Salvador DalÍ – "The Temptation of St. Anthony" (1946) | © Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres | photo: J. Geleyns - Art Photography

Salvador Dali, and this will come as a surprise to no one who has seen one of his paintings, tried to spend as much of his creative process asleep as possible. More specifically, he attempted to induce hypnagogic states, or semi-slumbers, from which he could draw inspiration.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/acee394fdac1b0b46025243715dc0ae3e5613050-1024x768.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=512)

Sleep by Salvador Dali (1937)

He went about this in a number of ways. Sometimes he would simply stare at his hand for a protracted period. Sometimes he would hold a heavy metal key over a plate and allow himself to fall asleep only to be rudely awakened by the key’s clanging to the plate’s ceramic. He called this the ‘slumber with a key’ method, which is good indication of why his painting survived longer in the cultural memory than his writing.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/d5cf894dfaa736d60ea2cf69a869b3a805de9af1-1280x998.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=640)

Philippe Halsman's surreal portrait of Salvador Dali. "Dali Atomicus." 1948. © Philippe Halsman | Magnum Photos

From these states of dreamy disorientation, Dali would extract inspiration for his works. Sometimes small details, others larger compositional makeups.

Practice physical rigor

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/6d9d6a5e90d93ac5d77279a5f0765ec594661aac-1280x902.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=640)

The Tilled Field by Joan Miró (1923-1924)

The body, the soul, the mind. Whether you think they are three distinct things or stylizations of the same one, the interconnection is indisputable. Physical vigor has been an asset to creatives since time immemorial. We used to have warrior poets, you know.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/89918edca99b2640774e4659dfa619a1cc64d932-2032x1355.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=1016)

Installation view of "Miró the Sculptor: Elements of Nature" Photo by Kent Pell. Art © 2020 Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

We also used to have Joan Miró, who religiously followed up his morning work session with exercise. In addition to the creative windfall of the physical stimulation, Miró hoped his routine would help keep the depression he experienced as a boy at bay. This is another lesson: as romantic as the tortured and melancholic artist is, they usually don’t make much. Most die in obscurity. Miró died at 90 of heart failure. So get in the gym.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/612a72e362fe3ed2c4ad171d1c32abd61d2ef5e5-1361x2000.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=681)

Balthus (Baltusz Klossowski de Rola), Joan Miró and His Daughter Dolores, October 1937-January 1938 / Credit: Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Fund / Copyright: © 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Consume your medium

One of the worst things a creative can do is be uneducated in their own medium and fail to take inspiration from the great works of their field. We all know the guy who fancies himself a painter but couldn’t name 5 non-pop-artists with a gun to his head, or the novelist who doesn’t think of himself as a ‘reader.’

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/8089c593f8df58bd26b7653e272bf1d5c4372f5e-1821x1821.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=911)

The Kim family in Parasite. Via NEON + CJ Entertainment

Maybe it works for some people. For most, it’s advisable to consume plenty of the medium you’re creating in. Take director Bong Joon Ho, best known recently for his 2019 film Parasite, who rises at 5AM every morning to begin his day by watching a movie. A movie before breakfast. Perhaps not feasible for all of us, but a nice idea. He’s probably seen more movies than the rest of us, and this is probably a good thing for his movie-making career. So carve out some time in your day and get wise about the history of your field.

Procrastinate

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/8f76f55babd83ce26af8400b647c79137f901d02-800x529.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=400)

Film still from Gerhard Richter: Painting, 2011. Dir. Corinna Belz, Zero One Film, 2011 © Piffle Medien, Berlin © Gerhard Richter 2017

Sometimes it takes a back against the wall. Gerhard Richter was like that. He’d go to his studio, fuck around for a few hours, and then, most days, leave without doing any painting at all. “I love playing with my architectural models,” he once said. “I could spend my life arranging things.”

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/72ddfeacee42fe66c5b2ee9f3d3b3207c134ac6f-3200x2134.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=1600)

Gerhard Richter, 4096 Farben, 1974, via Sotheby's.

There would come a point when his pent-up anxiety would break open, and in a state of crisis the artist would finally work. He didn’t have a particular issue with this way of working. To Richter, it was a danger to wait for ideas to come. Ideas had to be hunted. Sometimes, don’t wait for inspiration to strike you. Sometimes, go strike inspiration.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/515a6e98d5a8606aac25c848ba2d5d2b45c4a1de-1920x1280.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=960)

Gerhard Richter, MV 133, 2011, detail, lacquer on colour photograph, 10.1 x 15.1 cm © Gerhard Richter 2023

Respect the work

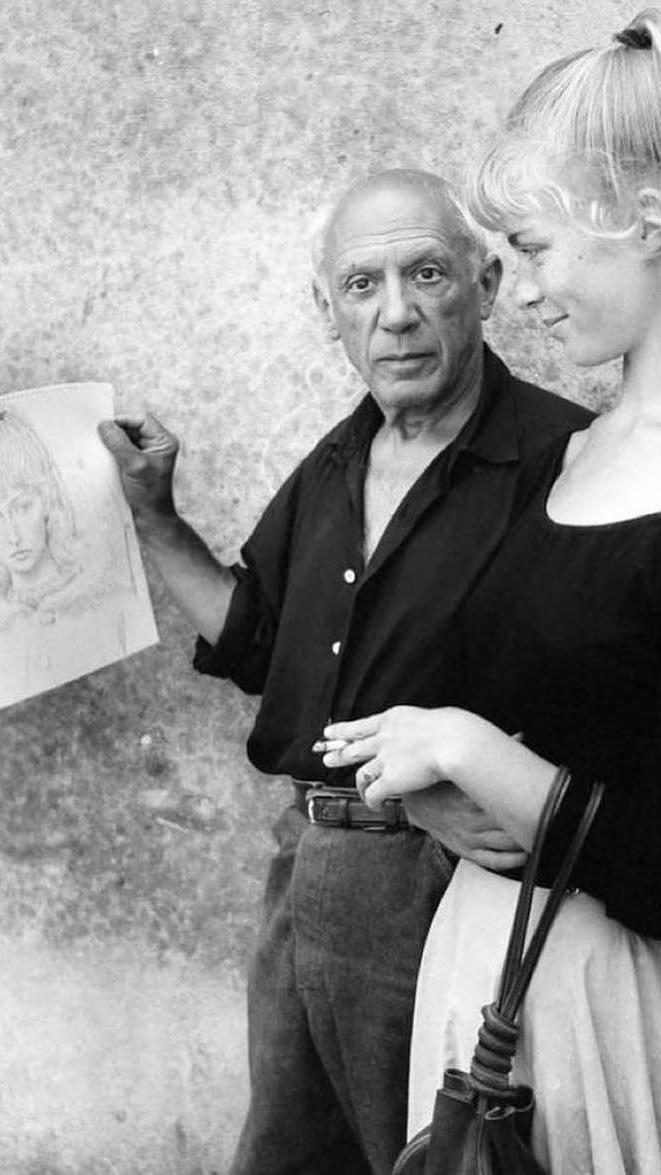

Balthus, the French-Polish modernist, was notoriously tightlipped about his personal life. He directed the Tate Gallery to introduce his retrospective displayed there with “Balthus is a painter of whom nothing is known.”

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/d7fa272a32c207e024c8cad68bd17a701ff62ece-1920x1200.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=960)

Balthus, Thérèse sur une Banquette, 1939. Oil on board.

What did emerge of his routine came mostly in his later years, and illuminates a man with a great reverence for his work. Every morning, Balthus assessed the sunlight. He refused to paint in anything less than perfect lighting. If the light was suitable, he positioned himself in front of the canvas and said a prayer. He would then stare at the blank or unfinished work and smoke, sometimes for hours, meditating on the task in front of him. Then he would begin.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/547fb820a88cd48778050c0d174186d603f6428c-2230x2560.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=1115)

Balthus, Thérèse Dreaming (1938).

Trying to make something is no joke. We should consider ourselves lucky if we are able to make a handful of great things in our life. A little prayer is probably in order.

Image Curation by Carly Mills