What Modernism Can't Teach Us

We the modern subjects, among the products of our possession and buildings of our residence, in the built jungle of essential and aesthetic objects we call home, are not, on the whole, impressed with the way things look.

Many have had cause to ask how it happened, where we should go. Many more have simply bemoaned. It’s everyone's fault–the corporations and the designers and the tasteless masses and the venture capital and the supply chain and the death drive.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/b98f728d06ddcb9c43df522e1bc699bd744bbffc-1600x1398.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=800)

1908 Singer Tower replaced by the 1973 One Liberty Plaza (via oldamericanarchitecture)

In these pages (pixels) you may have read previously about the nostalgia-response to this state of affairs. Escapist turns to minimalism, maximalism, the handmade, colorful, colorless. Many travelers have ended their march of disillusionment kneeling at the feet of modernism’s titans, among them those of the Bauhaus.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/950e43b95a849588f1db9dcbefe0c0349c6ec065-440x520.png?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=220)

Bayer's Bauhaus typefont

There's much to venerate there, but no answer to our predicament. If anything, there is blame to assign. Modernism, a movement founded on limitations we do not face and whose implications have in large part given us the public design we hate the look of, has little to teach us. Optimism about new materials and industrial capabilities, obsession with efficiency, and forms subjected to functions cannot define the design of our age. Our age asks us different questions.

-

Because today’s default disposition toward industrial mass production is one of explicit revulsion, it’s hard to imagine a time when the design avant-garde thought that industrialization could deliver an aesthetic utopia.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/5c2d751ed46c07d67e3ec77d1a0d82cba11c5f3f-3872x2592.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=1936)

The restored Bauhaus Dessau / Spyrosdrakopoulos, CC BY-SA 4.0

Staatliches Bauhaus, commonly Bauhaus (which is just ‘building house’ in German) was founded on this idea (among others) in 1913 by German-American architect Walter Gropius. Only operational until 1933, the Bauhaus emphasis on functionalism and multidisciplinary integration pushed a modernist agenda and inspired many of the 20th century’s titans of design. Throw a stone and hit a limb of the branching Bauhaus lineage, from IKEA to Muji, Helvetica to the iPhone, Dieter Rams to Zaha Hadid.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/f58bdebd9e325a902b7063e548487c2733e180d3-450x600.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=225)

Ani Albers's Eclat pattern

At its most general, the Bauhaus was an attempt to distill tenets of the burgeoning modernist movement into a single pedagogy. These tenants included integrating the artistic disciplines, dissolving the barrier between art and craft, and (their most famous calling card) form following function.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/e77d4435ea7067bf419265c18259dedcb1be2124-1471x1103.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=736)

Wassily chairs

Aesthetically, the school emphasized an unornamented and minimal approach, strong geometry and abstract composition similar to what had gained popularity in the fine art world at the same time. The concept of the ‘Gesamtkunstwerk,’ or ‘comprehensive artwork,’ was core to the Bauhaus approach; students at the Bauhaus were instructed in a general curriculum that included color theory and material practices before moving onto specialized study.

It didn’t last long, but in 14 years the Bauhaus production was impressive for its breadth of medium, its formal quality, and its prescience.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/fc78dcef6104bdffc3f6443329358a2e1bf5d8cf-1615x1443.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=808)

Keler's 'Cradle' / CC BY-SA 3.0

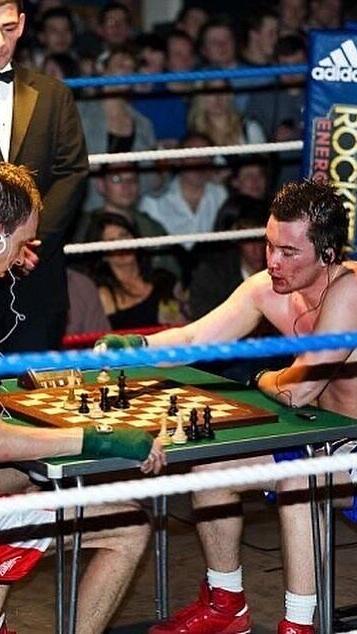

Some products, such as The Cradle by Peter Keler, Josef Hartwig’s Chess Set, and Marianne Bradnt’s tea infuser, still stand out for their formal inventiveness. In most cases, Bauhaus designs are striking in how unoriginal they look to us today, a testament to their influence on contemporary design.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/665a961e8bbab07df57415a0de2ba671f49ebd7f-2448x3049.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=1224)

Hartwig's 'Chess Set' / Noahhoward, CC BY-SA 4.0

The Wassily and Barcelona chairs are two of the school’s most famous furniture pieces, and would be perfectly at home at Crate and Barrel. Gropius himself designed a door handle that looks basically like most door handles today. Josef Albers’s nesting tables are saturated and we’re all constantly subjected to textile art in large part because of the work Anni Albers did in the format. Herbert Bayer was tasked in 1925 with designing a Bauhaus typeface. At a time when heavy gothic letter form was still ascendant in Germany, Bayer’s minimal sans-serif and non-capitalized font was fairly radical, if you can imagine.

-

Bauhaus has become a brand, a band, graphic tees and posters, a well-received film. It symbolizes, for many Americans, the avant garde, a quintessential entry in the western creative tradition, an aesthetic height that exists outside of history. Few associate it with a contemporary design mainstream that is almost universally reviled.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/d6bc588a3de9d6bba3a0a97c23c6a892d6263412-2636x3714.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=1318)

Walter Gropius

Its privileged status is attributable to a number of factors. One is that Gropius was an even better advertiser than he was architect. The Bauhaus image was carefully curated from an early stage, and the Nazi’s shutting it down was the best thing that ever happened to its legacy. The school became a martyr for the democratic cause, and many of its major figures moved to the US where an elite starving for any drop of European refinement welcomed them with open arms, immediately installed them in major cultural and commercial stations, and began producing their designs with an alacrity unmatched by their home countries.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/48c3547c23ac3526d221a348fe3e8c769faafb07-4680x3120.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=2340)

The Bauhaus Museum in Dessau - one of many institutions preserving the legacy

Even more impactful than these individual acolytes were the new movements that sprung up on the Bauhaus seed. Entire eras and stylistic umbrellas are explicitly Bauhaus inspired: Scandinavian, industrial, mid-century modern. The International Style, which is as responsible as any other aesthetic program for our downtowns, was a spin-off spearheaded by Bauhaus director Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/71704d2c9236954bc0d0fb98ea499bb8c36983e3-1024x680.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=512)

A flattering look at the International Style

Beyond the favorable ideological conditions it found during and following the war, modernist design was also at a material advantage. Initially couched in a socialist politics, the explicit goal of much of the Bauhaus production program was to make things cheaply. It was theoretically for the workers’ benefit, not that the workers’ were ever asked what they thought about this. This all sounded pretty good to a corporate world increasing in its factory lines, automation, and middle class. The Bauhaus vision of design and architecture was easy to make, easy to copy, easy to deploy in just about any case.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/bb5ce29c8d954a4adfd9f6235b15c7c39308c179-2399x3453.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=1200)

Herman Miller ad (1965) / Designer: George Nelson (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Crucially, it required far fewer skilled laborers. In this way it was a pernicious style, designed to succeed at the expense of the others by draining the industry’s capacity to make them. It offered a highbrow and cultured justification for cost-cutting, supply-chain narrowing, worker obsolescence, growing profit margins.

–

One shouldn’t overassign blame. Neither the Bauhaus nor modernism is accountable for what capitalism has always done. A more just examination of the school would be conducted on the basis of its actual design philosophy.

Which wasn’t very innovative. The ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ was lifted from Wagner. Form following function is a minor alteration to the balance of values architecture and industrial design has acknowledged since at least Vitruvius's 1st century triad of ‘utilitas’ ‘firmitas’ and ‘venustas’ (‘utility’ ‘strength’ and ‘beauty’). Bauhaus’s wasn’t even a particularly radical articulation of functionalism. 19th century English designer William Morris declared no distinction between form and function at all.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/76f6e70b5871c6f52fe77d65165c917bfa06a3c3-1296x1296.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=648)

Albers's 'Nesting Chairs'

If the Bauhaus has any conceptual legacy, it is a philosophy of subtraction. Minimalist functionalism has a long lineage, but the Bauhaus approach to the idea was particularly influential. Mies van der Rohe, during his time as director, coined the term ‘less is more,’ something that became a foundational line in the minimalist manifesto.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/7565ce1faa2b2624b9d43b14844b610a43f361aa-2000x1125.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=1000)

The distinguished Mr. Rams sitting afront his wall-mount speaker system from Rams, directed by Gary Hustwit. Credit: Gary Hustwit

The Ulm School of Design was basically an attempt to refound the Bauhaus under a different name, and picked up the minimalist torch with a passion. The school’s work on Herman Miller and Braun products remain iconic. So does the name of one of their key collaborators: Dieter Rams. Rams is the reason iPhones look the way they do. Not only Jonathan Ive but also Jasper Morrison and Naoto Fukasawa are stylistically indebted to him.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/44bdef51e01837784c163b9dce7f96ecab1810cb-800x505.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=400)

Braun & Apple side-by-sides / CC BY-SA 4.0

People love Rams’s work. It’s easy to see why. He took Mies’s philosophy a step further. The 10th principle of Rams’s 10 principles of good design reads: “Good design is as little design as possible.”

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/f61f07882fb69a980744ff40d250f8defc1e70d5-747x900.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=374)

PeterAjtony, CC BY-SA 4.0

When he wrote this, there were still many constraints on that minimization. Design was visible, definitionally so. Rams made radios, calculators, tape players, lighters. But now radios are apps, and calculators occupy nanometric space on our phone chips, and tape players are antiques, and lighters are a soft glow behind colorful plastic casing. The crux of future design occurs in a space invisible to the user, microscopic parts on the hidden side of smooth surfaces. If form takes its cue from function, what happens when function no longer requires form?

-

We all want to know what the design of our age will look like. We aspire to be an era, to have an entry in the ideological lineage. This may be too much to ask, but a good place to start a hopeful search is our technology. Technique, tool, and technology have been central drivers of every aesthetic era. Ours is a technology of nothing, of invisibility.

Modernism leveraged technology to break down existing material limitations and postmodernism threw a wake to celebrate their death. The party sucked and the party is over, the limitations are rotting in the casket. Their absence is left in the shape of a choice.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/69d4608195dd2ef3b0355623bca9791441db7f39-4608x3456.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=2304)

Josef Albers' Studies for Homage to the Square

If we want to have any at all, new materials and production processes and functional streamlining cannot define the design of our age–choice must. Not a philosophy of subtraction, but one of addition. When you can make anything, what do you make? When you need nothing, what do you choose? Our curse and our opportunity is to decide.

Image Curation by Carly Mills (@carly_monoxide)

Written by Noah Jordan (@nnoahaonn)