Miguel Adrover: Against Commercial Fashion

“Half of my life, I've been hiding and coming up, preparing an attack”

(Miguel Adrover, 2011)

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/1966a45e7d4bed645e51533ba7836bccc5a24fc0-1800x1800.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=900)

Miguel Adrover at his home in Mallorca, Jan. 8 2024. Photography by Catarina Osório de Castro

Fashion has long been associated with exclusivity, status, and luxury. Miguel Adrover imagined a different source: creativity and the ordinary. Rising to prominence in the early 2000s, he repurposed found garments such as thrift store finds, work uniforms, and even designer pieces into high-concept fashion, rejecting the industry's obsession with elitism and commercialism.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/6cd28b321cd0a8ff937bc071dbde3dabfa21bbdb-1080x1346.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&rect=0,156,1080,1140&w=540)

Adrover's famous ballcap sweater (printed "MA" after the initial copyright debacle) in archive via Instagram (@west__archive).

Despite his influence, Adrover’s refusal to conform to commercial pressures led to his downfall, while luxury brands later profited from similar ideas. His work raises an essential question: can fashion ever escape elitism? or will the industry always commodify even its most radical innovations?

-

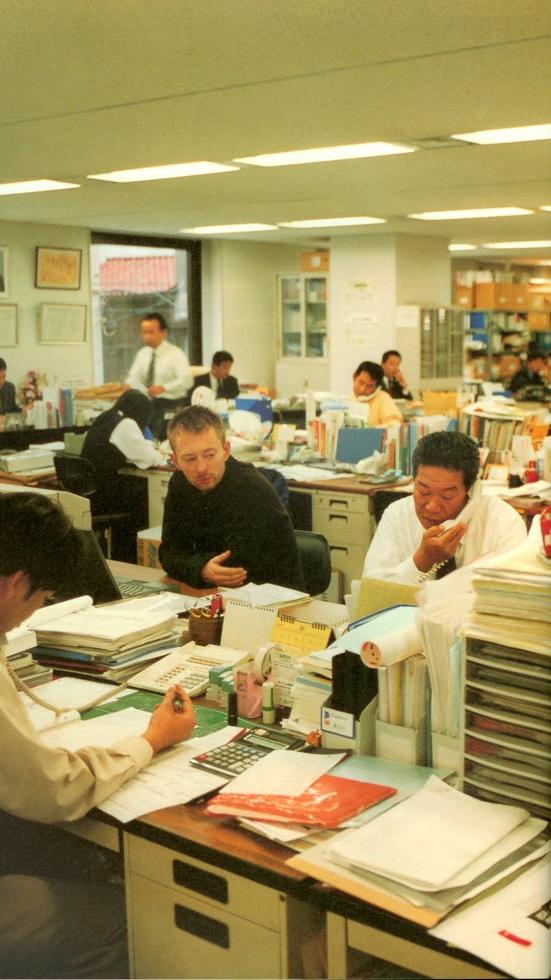

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/c297bb49faea9b3855a736c3e27ff91b273212b9-980x600.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=490)

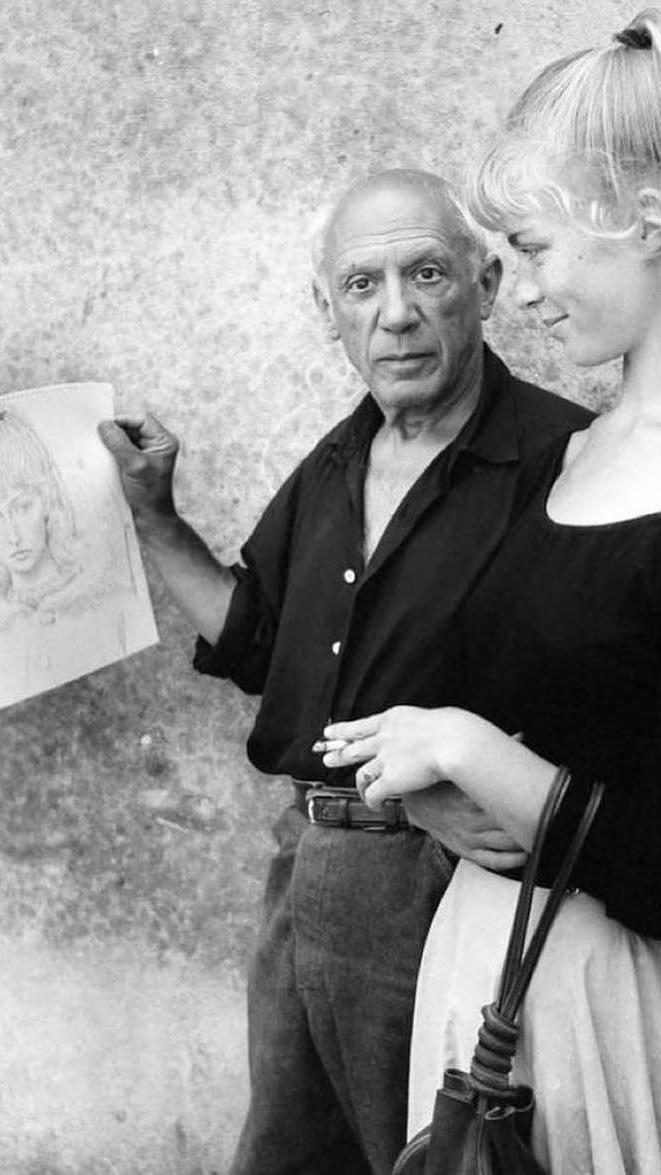

An early photo of Miguel Adrover and designer Lee Alexander McQueen in the 90s. Photography by Juergen Teller

Miguel Adrover was born in Mallorca, Spain, 1965. He received no formal training or schooling in fashion. His interest in the industry began with a trip to New York in 1991, where he decided to stay, enamored with the cultural diversity and avant garde fashion scene.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/3c6be18f405f61cc9de8dd3c24f96ff47d67e26c-720x900.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=360)

"Manaus - Chiapas - NYC" (1999) via Instagram (@migueladroverofficial)

In 1995, Adrover and his close friend, Douglas Hobbs, opened Horn, a boutique store highlighting independent and underground designers. After the store's closure in 1999, Adrover debuted his eponymous label in a runway show titled “Manaus - Chiapas - NYC.”

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/fa7b86f124f1f3a2ae02c5ed43090072d90edda4-878x1166.png?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=439)

Karen Elson wearing a piece from Adrover's debut collection for Dutch Magazine, January 2000. Photography by Thomas Schenk

The Deconstructed Trench: Deconstructing Luxury

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/90072cc0fdb2e1954f2b99485c0cadd02252912c-1080x1080.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&rect=0,28,1080,1052&w=540)

Reworked Burberry pieces from "Midtown"

(2000) via Instagram (@migueladroverofficial)

One of Andover's most famous pieces is his reworked Burberry trench coat, ‘Trench Coat,’ from his 2000 “Midtown” collection. Instead of treating the coat as a sacred luxury item, he deconstructed it–turning it inside out, re-tailoring its shape, and presenting it as something entirely new. Burberry, a brand associated with British aristocracy and wealth, suddenly became part of a gritty, subversive fashion statement.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/5c031d0e1a1831a3aab62509baefca5fe5e907a9-1080x1350.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=540)

The iconic coatdress from "Midtown" (2000), runway details via Instagram (@archivepdf)

This look was a direct critique of the way fashion brands build exclusivity around logos and heritage, replacing luxury’s focus on status symbols with one on craftsmanship and reinterpretation. Adrover stripped away prestige in favor of new meaning. Years later, designers like Demna Gvasalia of Balenciaga and Vetements would use similar strategies. Unlike Adrover, the industry embraced these designers.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/3425cfd23c5529d899f5814a4c12b19723df019b-1080x1080.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=540)

Models Karen Elson, Liya Kebede, Maggie Rizer, Caroline Ribeiro, Colette Pechekhonova, Missy Rayder And Malgosia Bela dressed in Adrover's "Midtown" collection for Vogue (2000). Photography By Steven Meisel

Baseball Caps: Elevating the Everyday

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/e0162ca20635cc8cdac5b0bbbd3cb5be957299bd-1097x1350.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=549)

Photography by Miguel Adrover via Instagram (@migueladroverofficial)

Another rejection of fashion elitism was Adrover’s baseball cap sweater, which featured two baseball caps as shoulders. At a time when expensive materials and meticulous tailoring defined fashion, Adrover used mass-produced everyday accessories associated with casual street style and working-class identity. By doing so, he challenged the connection between luxury and expensive fabrics.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/ed91a9524e02b759e7a2d2060f0c07a038530515-1097x1350.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=549)

Self-portrait wearing the ballcap sweater from Fall/Winter 2000 via Instagram (@migueladroverofficial)

While brands like Balenciaga and Vetements have embraced sportswear and everyday items, their approach turns streetwear staples into status symbols for the elite. Adrover's was more defiant–he wasn't just appropriating an aesthetic, but critiquing fashion's obsession with exclusivity. His work questioned why branding and social status should dictate an item's value, rather than innovation and artistic vision.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/19b1a8376c60ae16310c2d892eb39aa49d1ea1dc-1080x1349.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=540)

Self-portrait via Instagram (@migueladroverofficial)

Androver's Critique of Commercialism And Elitism

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/cc0872150cea4af34bf2fb8bf8b4c8f74834ab82-1280x853.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=640)

Self-portrait for Vogue, 2019

Adrover’s approach challenged the idea that fashion should trickle down from luxury brands to consumers, instead showing that streetwear and thrifted garments could be just as stylish and meaningful as high-end fashion. His work foreshadowed today's rise of streetwear in luxury fashion, but at the time, his ideas were too radical for the industry to fully embrace.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/4ec955aa7762b55e070e3d0b23b5f0fad38d156e-1080x1349.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=540)

via Instagram (@migueladroverofficial)

Miguel Adrover's work was not only a rejection of fashion elitism but also a direct critique of increasing commercialization. During his career, luxury brands were becoming more focused on mass production, celebrity endorsements, and brand recognition. Adrover remained committed to an approach that prioritized creativity over profit. His collections demonstrated that true innovation did not come from expensive materials or logos but from subverting expectations.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/3044adbf471f2099c19788f30fd855e9e85ca0d5-897x1350.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&rect=0,16,897,1315&w=449)

via Instagram (@migueladroverofficial)

One of the clearest examples of his anti-commercial stance was his SS 2002 collection “Utopia,” which was created as fashion accelerating in both globalization and profits. Instead of catering to industry trends, Adrover drew inspiration from Middle Eastern and Indigenous cultures, incorporating traditional craftsmanship into his designs. He aimed to celebrate cultural diversity at a time when the fashion world was increasingly dominated by Western luxury brands that appropriated these influences without acknowledgment. However, rather than being embraced, the collection was met with resistance, especially in the post-9/11 political climate.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/ddea278a26bed5577447434077cb2303ecbdd351-1080x1326.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=540)

A piece from ''Utopia'' (2002). Photography by Max Von Gumppenberg

Additionally, Adrover refused to conform to the fashion calendar's relentless demand for new collections. While other designers adapted to the pressures of producing seasonal trends to maintain financial success, Adrover worked at his own pace, refusing to compromise his vision for commercial viability.

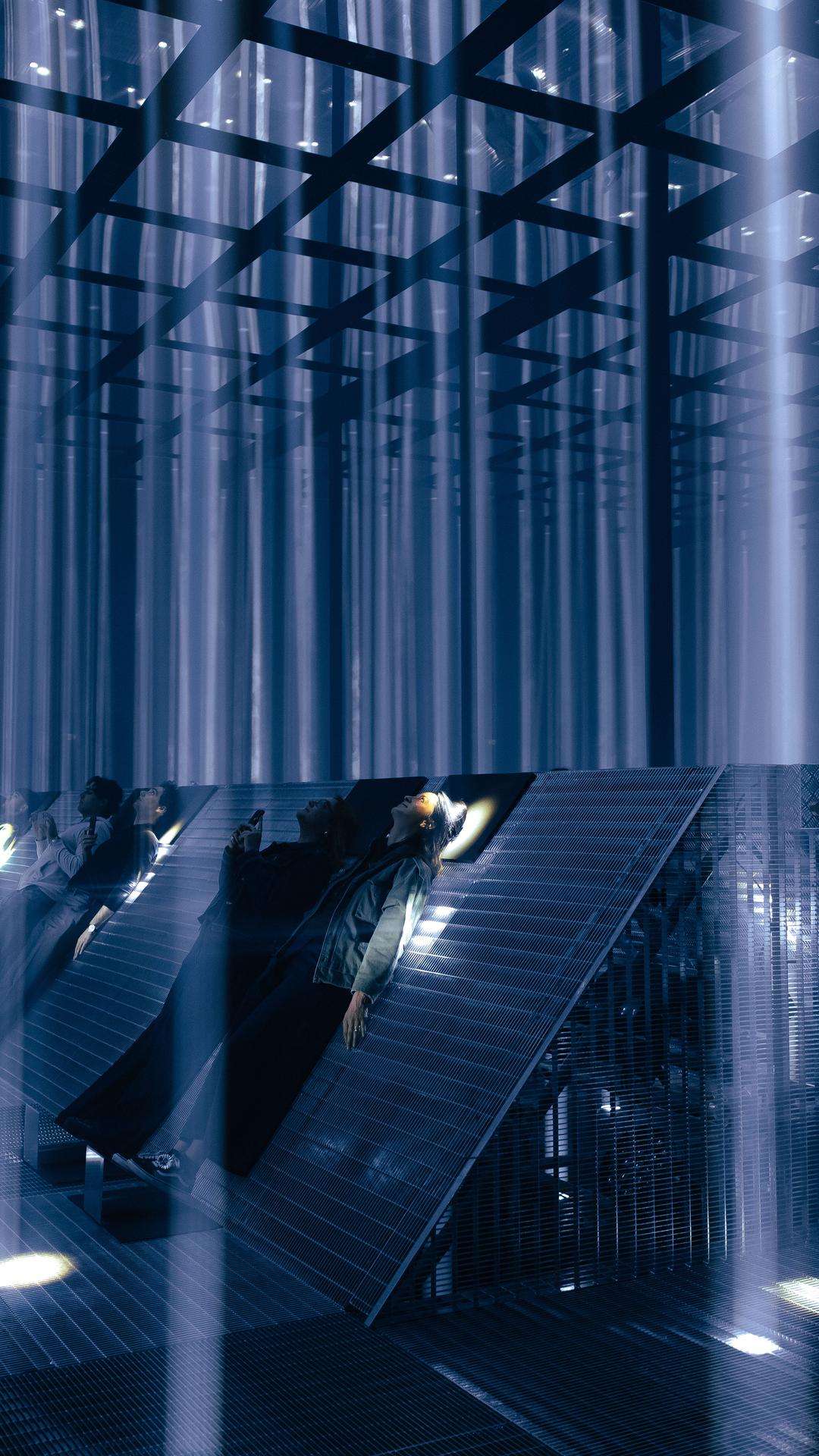

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/b1a506f8bc428b30fabb5bab41b63a0e0eac5fc6-720x900.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=360)

Behind the scenes at "MeetEast" Fall/Winter (2001). Photography by Alex Cayley

Of course, Adrover's focus on upcycling and sustainability–once seen as radical– has now been embraced by major fashion brands who market their sustainability efforts as a selling point. Adrover wasn't creating sustainable fashion to appeal to customers or boost sales; he did it because he believed in reusing and repurposing materials as an artistic and ethical statement.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/7e8ca2514aa133adf38879a686b49b470772c2a3-1080x1350.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=540)

via Instagram (@migueladroverofficial)

Ultimately, Adrover's critique of commercialism highlighted a core contradiction within the fashion industry: while it claims to celebrate innovation, it often stifles those who refuse to conform to its commercial expectations. His career serves as proof that fashion, at its best, is about creativity and storytelling–not just profitability.

The Commercial Reality and Adrover’s Downfall

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/bf0b7b069438baeedb805df92246433c07397d4f-1370x2048.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=685)

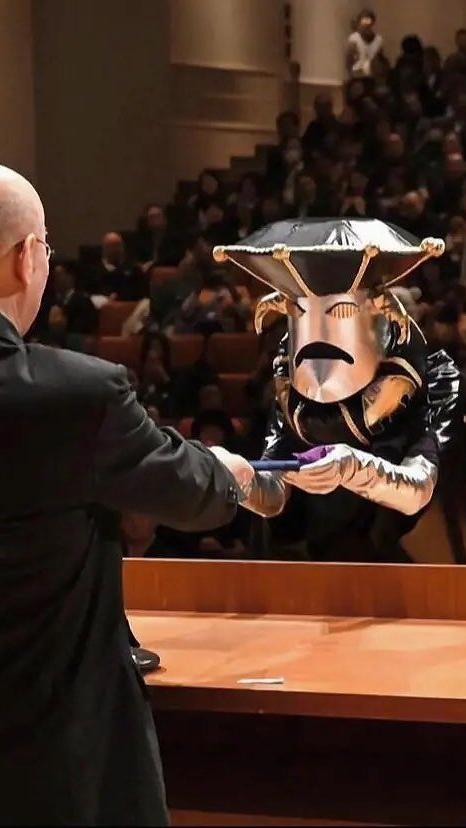

Adrover closing out his Spring/Summer 2005 show wearing an "ANYONE SEEN A BACKER?" shirt

While Adrover’s rejection of fashion elitism and commercialism was groundbreaking, some may argue that his downfall was inevitable in an industry that relies on financial stability and marketability to survive. The fashion world, at its core, is a business, and for designers to sustain their work, they must find a balance between artistic vision and commercial appeal. Unlike Adrover, many successful designers have managed to navigate this balance–embracing creativity while also understanding the importance of branding, production, and consumer demand.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/91e649cd691e9f12fe8a39b3da0d7c306e7abd54-828x1029.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=414)

via Instagram (@migueladroverofficial)

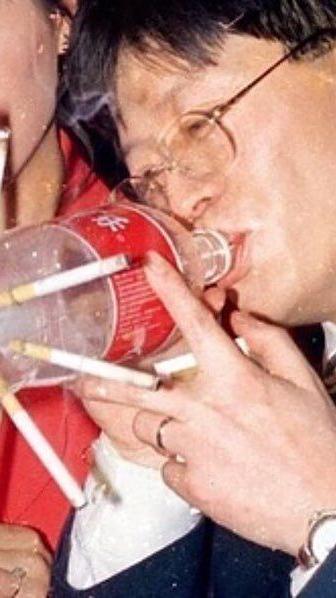

One could argue that Adrover’s refusal to compromise ultimately limited his longevity in the industry. Many designers who started with radical ideas, such as Vivienne Westwood and Rei Kawakubo, managed to maintain their avant-garde edge while still building successful global brands. Even designers known for their deconstructionist approaches, like Martin Margiela, found ways to work within the system.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/95e3d59ec0d4c94bde48f3daeefdf661ea3098c5-958x639.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=479)

Some of John Galliano's deconstructionist work for Maison Margiela FW16. Photography by Chloé Le Drezen

Moreover, Adrover was not the first nor the last to upcycle materials or deconstruct traditional garments. Designers like Jean Paul Gaultier and John Galliano also experimented with non-traditional fabrics and silhouettes but were able to package their work in a way that appealed to both the industry and consumers. If Adrover had found a way to balance his artistic ideals with commercial viability, perhaps he could have remained relevant without compromising his message.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/e0f34b9e21b31b755fb6d0ebe2b93273b9deb472-683x1024.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=342)

A piece from Adrover's Fall 2012 show, much compared to later designs from Balenciaga. Photography by Talaya Centeno

Some may argue that the industry has changed significantly since Adrover’s time, becoming more open to sustainability, deconstruction, and streetwear influences. Major brands like Balenciaga and Vetements have embraced similar ideas—reinterpreting workwear, upcycling materials, and playing with irony in luxury fashion.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/7a7df9850f1714b9808a04acfe08b6417888814e-2000x2500.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=1000)

Look 33 from Balenciaga's 53rd Couture Collection

But the question remains: can fashion exist outside the commercial system? or must even the most visionary designers find a way to work within it? Is it possible for designers to truly challenge the system without being absorbed by it? Or will fashion always find a way to turn even its most rebellious voices into just another trend?

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/afe345942415b074c7485bcd24ef25b8e0a51199-1080x1349.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=540)

via Instagram (@migueladroverofficial)

Written by Ben Kobayashi (@benkobayashii)

Image Curation by Carly Mills (@carly_monoxide)