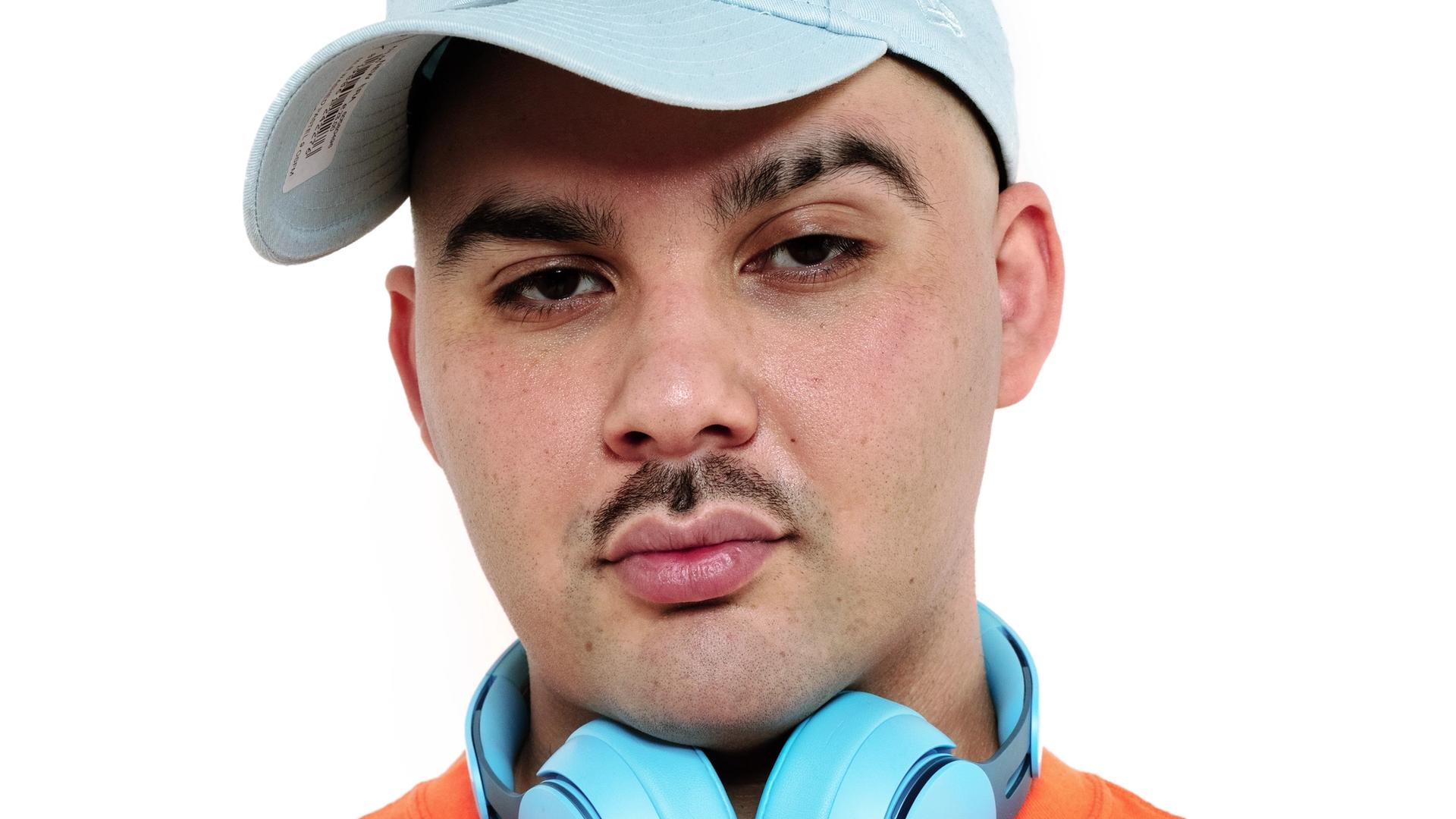

The Mechatok Interview

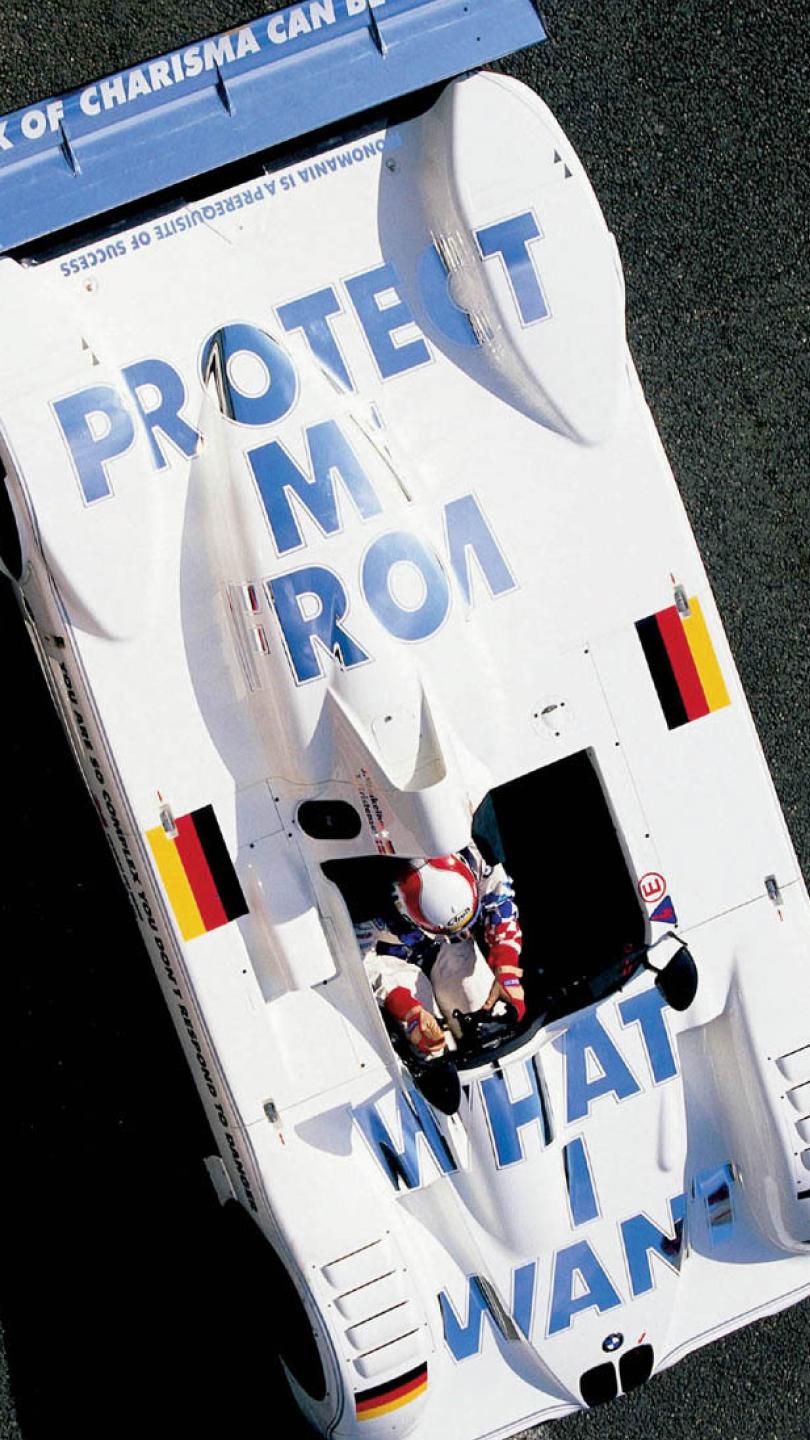

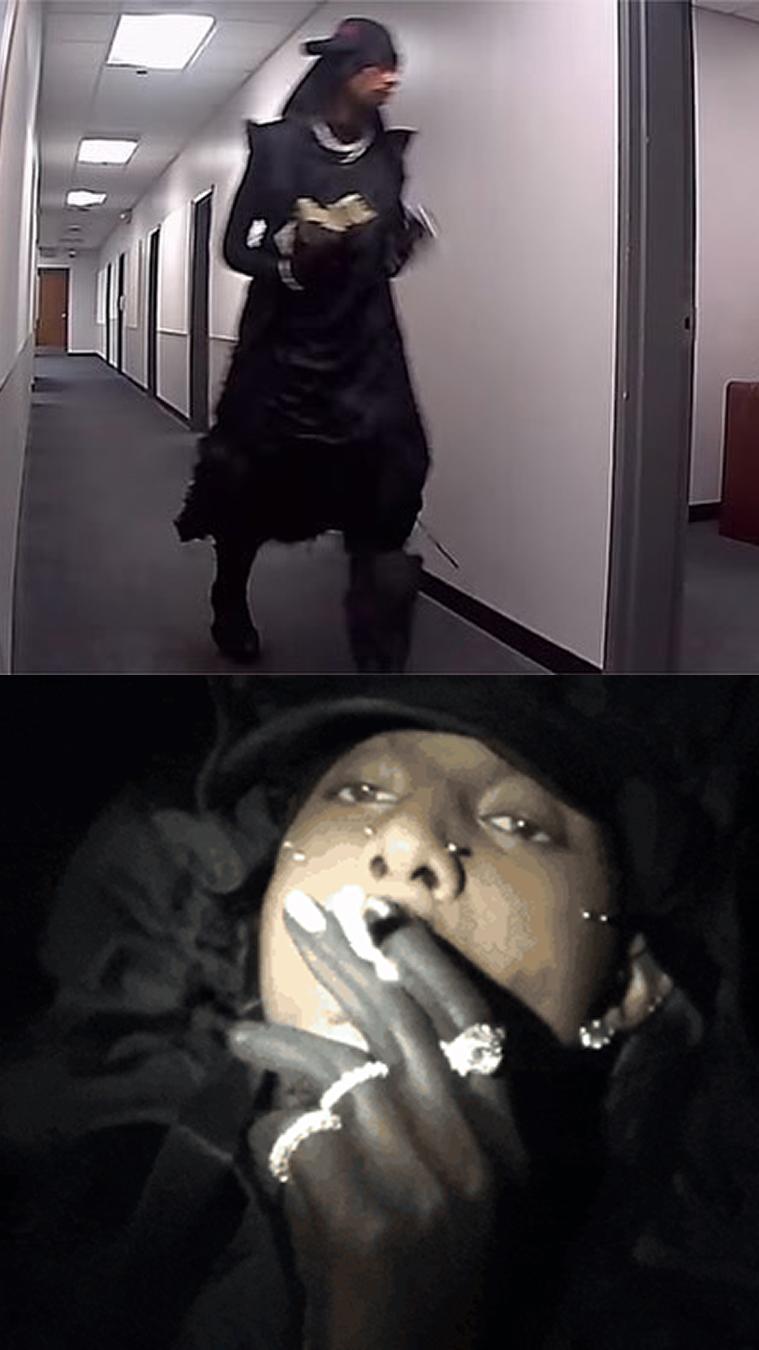

Cover photography @erikakamano / edit by archie barr @a7chie / wardrobe/styling by @a7chive

Sound is one of the less fickle senses. More assertive than smell, less deceptive than sight; our ears may lie to us less than any other organ.

But when it comes to the Sound of an era, an area, or a generation, the hearing is more complicated. Artists and enthusiasts trade ideas and inspiration in a largely unseen swirl occurring in the metropoles, clubs, bedrooms, and internets of the world’s youth. The prevailing trend has a long bend and isn’t easily dissected. It’s rare that someone has the longevity and the positioning necessary to help shape Sound’s direction.

For the last decade, producer and DJ Mechatok has been one of those rare sculptors. Hailing from Munich, rigorous early training in classical music did at least two things: give him a masterclass in notational thinking, and make the digital production interface he encountered in his teens a revelation he knew what to do with.

He moved to Berlin at 18 and made a name for himself. Particularly fortuitous friendships with Drain Gang affiliates gave us a collab album with Bladee and a handful of exceptional songs. Since 2022 he’s been pitching a wider tent with his Natural Mind event series which most recently gave us a night of Fakemink, Ecco2k, and Isabella Lovestory.

Mechatok’s integral role in several influential subscenes has made a real grassroots impact. This relative obscurity is going to be hard to maintain. He recently dropped his debut album. With features from the likes of Bladee and Ecco2k, the album is a crisp sound for a new era.

There’s history behind it. We spoke with Mechatok about it, and Sound, media, the algorithm, perfect days, hope, and more. Read on.

-

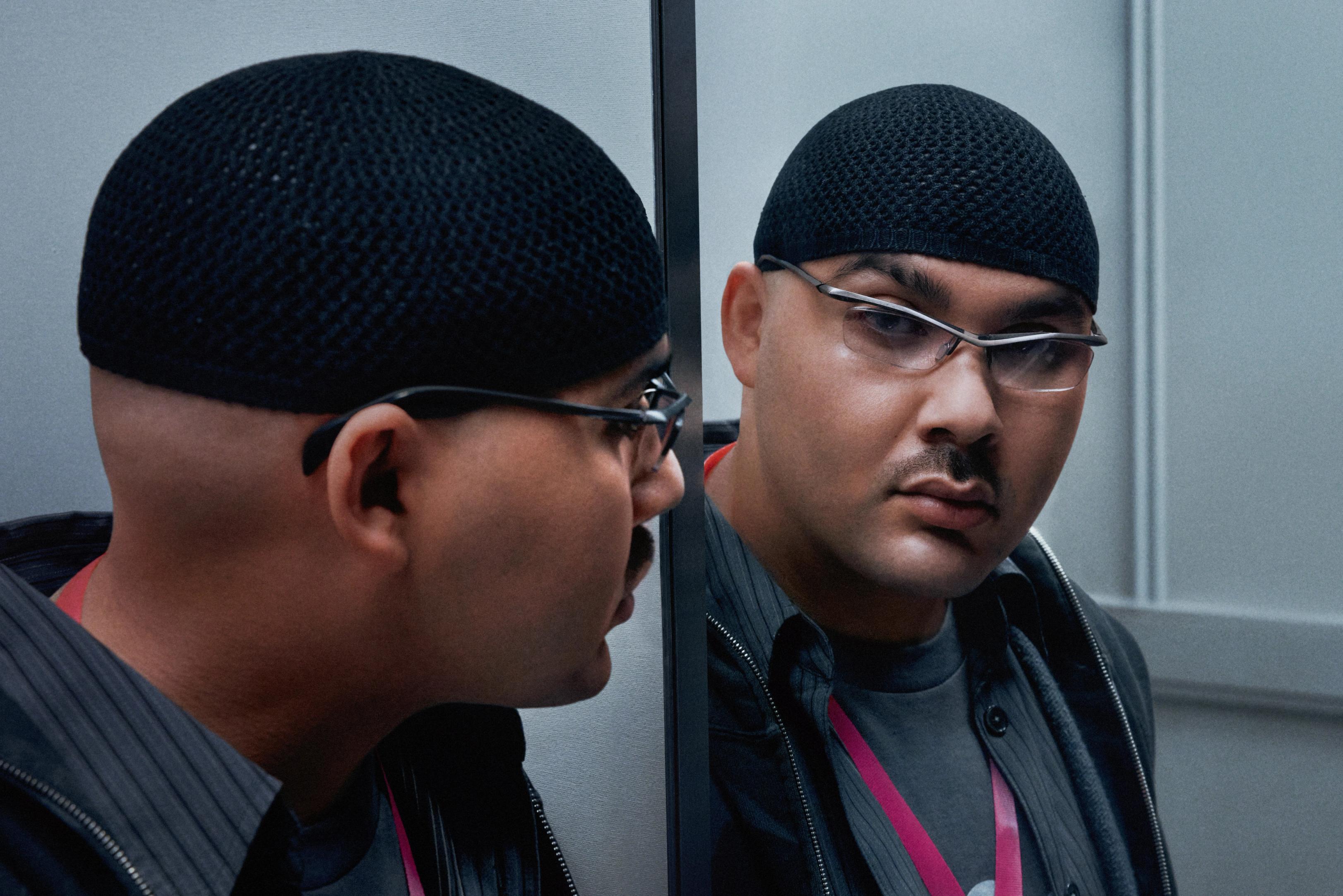

Welcome: What’s your story? How’d you come up, get into music?

Mechatok: I nearly became a professional classical guitarist. Early on I was doing competitions and was in the music university in Munich, but that world was conservative and annoying. I started making music on my laptop, which felt like a video game compared to practicing an instrument a couple hours a day. By 18 I moved to Berlin where I started DJing and dropped my first couple of EPs, electronic instrumental stuff. It caught on and I started touring. Around that time, I also started hanging out more with the Drain Gang guys. That led to us working together a lot.

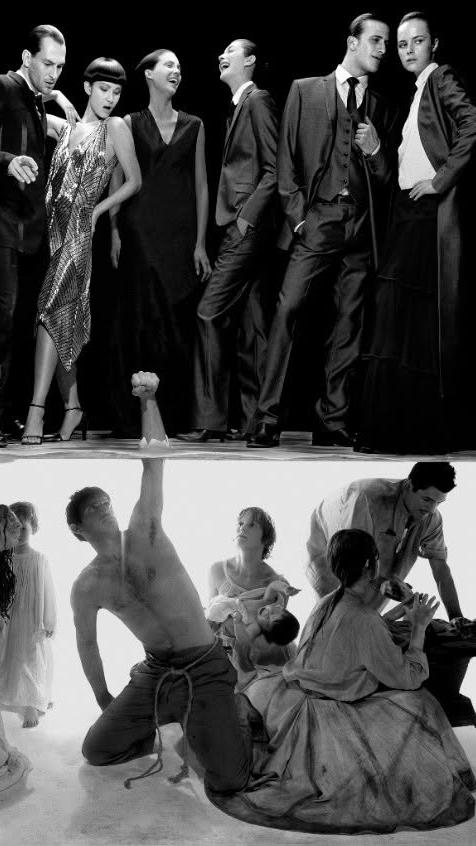

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/b745ba32c129abd56cb4b070528a3aaf30f75fed-6827x4885.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=3414)

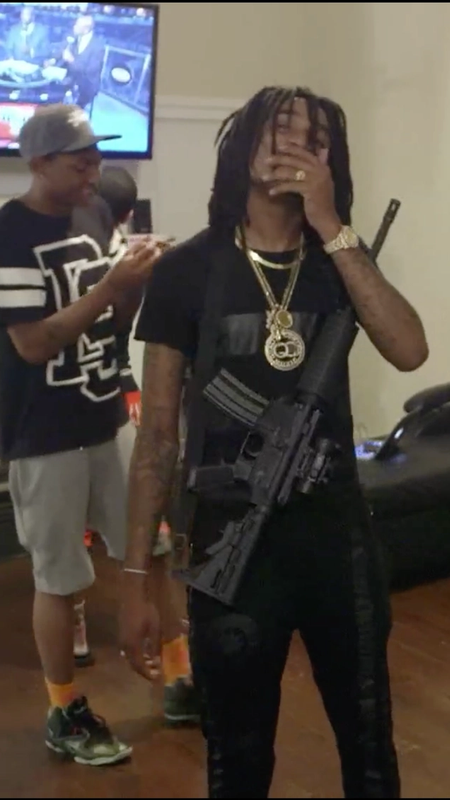

Ecco2k, Mechatok, and Bladee on the set of 'Expression On Your Face'

Welcome: How do your past classical studies apply to your musical practice now?

Mechatok: Rather than making beats, I work more like a composer. It's songwriting first, the rest comes after—sound design, synths, drums, etcetera. I always hope that you can cover my songs on guitar or piano and still get the essence. It doesn't rely on flashy production that much.

W: You mentioned that classical music culture was conservative. Now you’re in a very different musical world. Do you feel like in the creative culture you’re a part of now there is a freedom to express yourself?

M: Definitely. Now more than ever it feels like an absurd battle royale of ideas. People come out with a new type beat every two weeks. It's absurdly fast. Maybe you could say people should refine their ideas longer and not just jump to the next thing. But I like the idea of trying a new thing quickly. The environment now is really good. Maybe the way things are distributed is questionable—the whole hyper-algorithmic, turbo-competitive thing—but the creative end is so exciting.

What in your view has led to this current moment with so much fresh sound coming so fast?

If I had to make a theory, I’d say now more than ever, kids have very easy access to music from the past. They can pull from the 80s to the late 10s as references and it's all flattened on YouTube in the same recommendation bar—you might get Fleetwood Mac, then J-pop or something. Previously, with algorithms on SoundCloud, I’d get into one rabbithole and my feed would be hyperfocused on that. Now everyone has a super eclectic taste. Some might argue that to pull meaningfully from other artists you need to understand their full discography. But I guess you can just sample 10 seconds from a song you just found and put a drill beat under it.

You mentioned the pitfalls of the distribution side of this equation, and the role of the algorithm. What are some you notice as an artist?

A lot has to do with speed and quantity. If you're the type of artist who wants to take 3 years to make a record and chill for another 3, this environment works against you. Ideally you flood the algorithm with stuff every two weeks I guess. You exit the conversation quickly if you don't keep putting stuff up. Some solve this by being visible for other reasons than music. But artists who want to let their stuff simmer and refine it aren't being favored.

You just dropped an album. Were you thinking about these distribution and media conditions when making this project?

It’s an interesting project in the sense that it’s in a way both about these conditions, but also a product of them. I was inspired by getting my brain fried looking at all this random content on my feed. The record is about that, but it's not necessarily made for that context. But because it's related to it, it'll probably resonate there anyway. I care about my music being heard. I'm not the kind of artist who says, “This is genius, I don’t care if anyone hears it.” I do want to make things accessible. I definitely was influenced by how Reels and TikToks loop. I got into this idea of looping vocal mantras and doing these short, poignant statements that are both the song title and the main vocal sample. In that sense, yeah, it’s both for the algorithm and about the algorithm.

This is not the conventional feature-driven producer project. How did you approach features for this project?

There are two things that massively influenced how I approached vocals. One is Daft Punk’s Discovery. I always wanted to make a record like Discovery. It’s a movie and a beautiful instrumental project, but also a pop album. It does everything. It’s something I loved when I was eight years old and still love now. I love the way they incorporate other people’s vocals but it’s undeniably a Daft Punk song no matter who’s on it.

The second influence was this dark fascination with how K-pop is produced. That super manufactured thing with highly trained performers and a production team directing everything. Obviously, everyone on my record is a friend, so I’m not telling people what to do exactly. But there was a consensual version of that where I told everyone, “I really have an idea for this, are you down to join this vision?” For example, Isabella Lovestory did one of her rare English songs, sounding way more indie and much less reggaeton than usual. Bladee’s on an electro beat, which is not really his usual palette - and so on.

How does this project, Wide Awake, feel different from your other projects? What were the standout transformations that took you from Good Luck to here?

I got really tired of the sound I had going on. This project was more ambitious in the sense that rather than banging out a bunch of songs over a few months and picking the coolest ones, I set up a kind of narrative and rules for myself before finalizing anything. Sonically, the palette is a lot broader than previous stuff. I started using samples, which I never used before. I used to have these stoic rules about how my music was made, strictly synths, no drops. This one is much more free.

What is your process like?

I actually make tracks really fast. If I like the idea, it can be done in a day. The problem is liking the idea. I’ll have to make 60 shitty sketches to find the one golden thing that’s worth spending time on refining.

How long did you work on Wide Awake?

The actual making of the album—the 11 songs—took a year. But getting to the point where I felt confident to make it took way longer. In between, I was doing sound installations, producing other people’s records, design work, graphic design. Branching out in all those ways was like research. After the last record. I didn’t want to drop anything that didn’t feel substantial. Everyone has their own view of what that means, but in my head it made sense to try all these experimental things to arrive there.

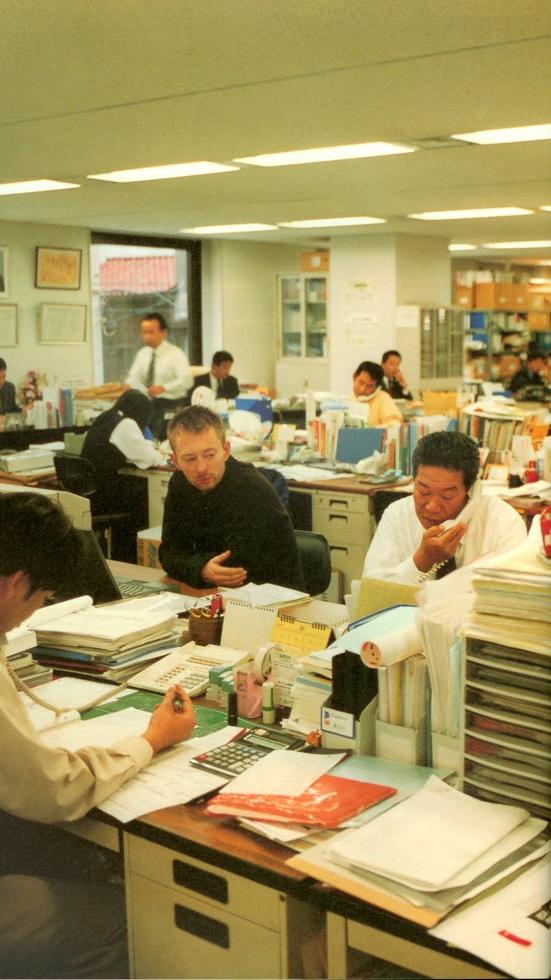

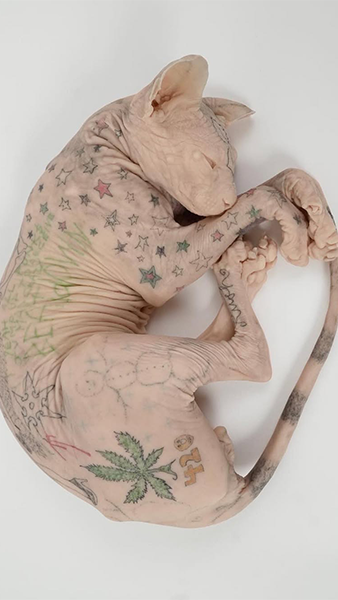

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/a45cae940bb475b78ef00e029ad1637d900837b5-4160x4160.png?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=2080)

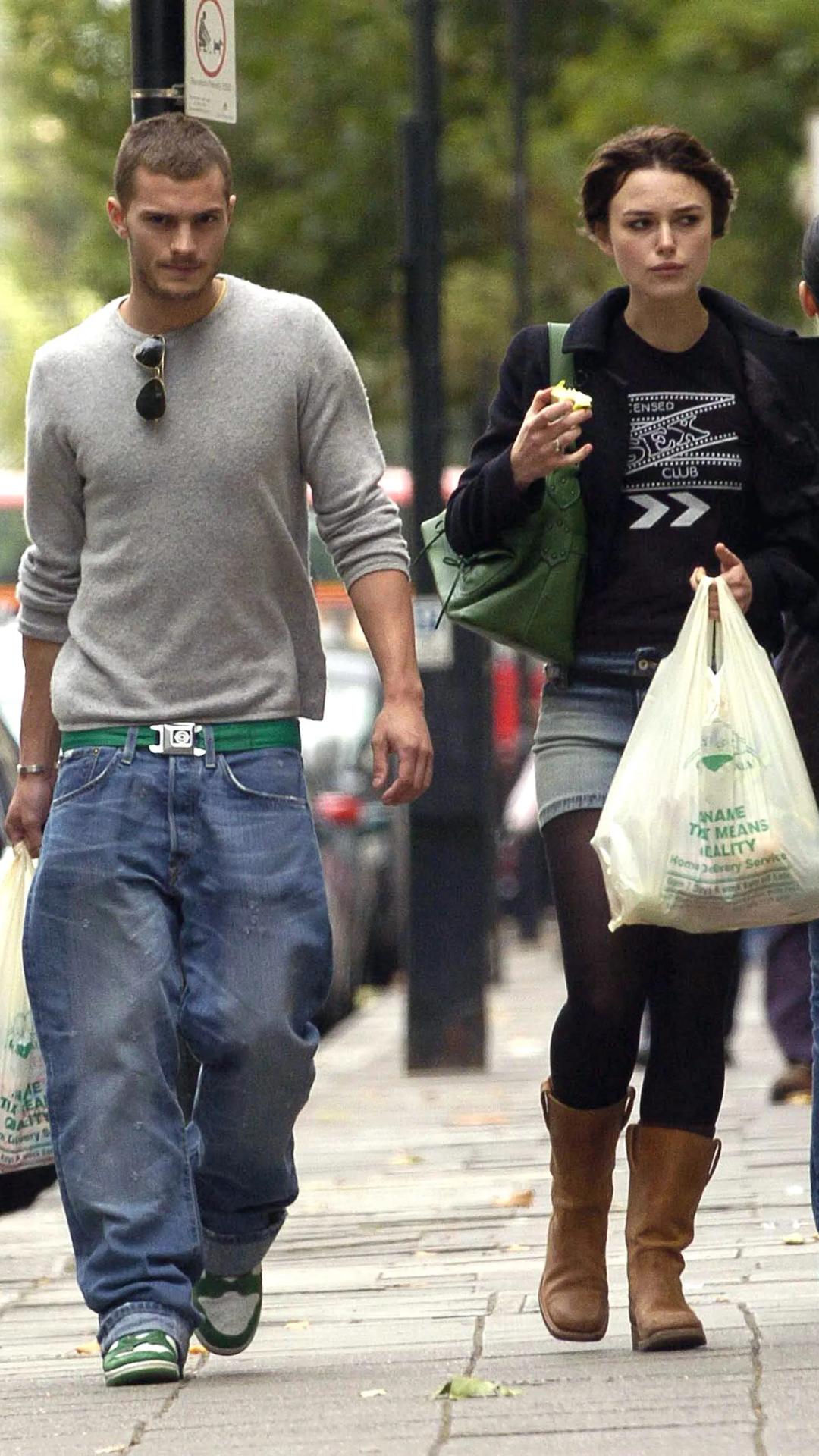

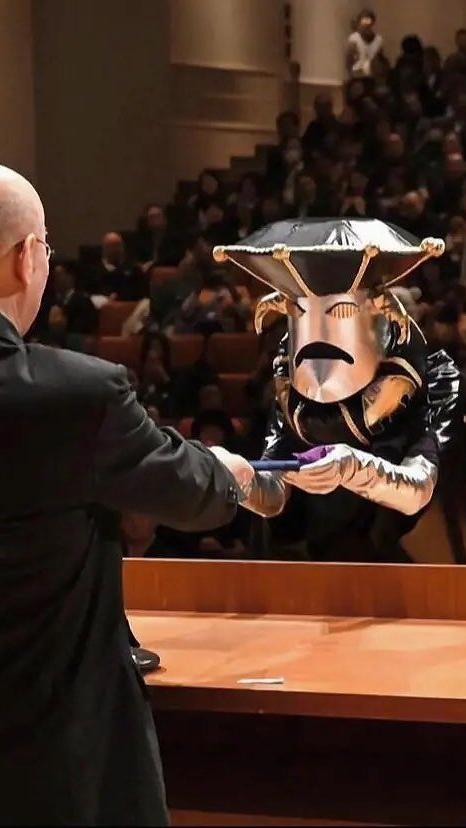

Mechatok at one of his Natural Mind events

One of the things you’ve been doing for several years is the Natural Mind event series. Tell us a bit about how that started and what it is.

Natural Mind started in London in 2022, not long after lockdown. I was asked to do a residency at a club and we decided to make it something special. There was always a “scene,” a loosely defined group of creatively aligned friends and artists—but we wouldn’t end up on the same lineups or even see each other that often. It’s just a vague sense of community.

Natural Mind became a way to give it a name. It’s a good excuse to bring all the friends together every couple of months. It’s not something I’ll do every month. It’s more like: if the stars align and the crew is around, these nights are a great opportunity to play new material or do something wild.

One time, we had a scissor lift on stage to install a giant balloon on the ceiling. The installation took too long, so the doors opened while the lift was still on stage. Ecco somehow knew how to use it and raised himself up during the performance. It’s literally a playground—a space to do things that wouldn’t fly in more corporate or conventional settings. Over time, it’s grown into a brand. It’s an outlet for my visual ideas as well.

What impact have friendships with collaborators had on your career and creative life?

If I go way back, there was a collective in London called Bala Club—very experimental, harsh-sounding stuff. Bala Club, Drain Gang, and my friends in Berlin made up this big circle. We’d always meet up in London or Berlin—everyone was like 18 or 19. It wasn’t that popular yet, it was very online. That’s how we all met—on a friend level. Following each other on SoundCloud. There was this shared aesthetic sense, similar humor, and an obsession with pop culture.

Later, Bladee moved to Berlin. During lockdown, we had nothing to do but make music at my place. Ecco came in and directed all the visuals for the project. We worked super closely for months. It was intense—we were trying to do so much: crazy merch, ambitious videos. That’s where we really bonded. So our friendship is cool because there’s so much to exchange on many layers—not just music. They both help me a lot. If I’m unsure about a visual decision, or vice versa, we can talk it out.

When it comes to visuals that accompany your music, how do you think about them? Are they complementary? Essential?

There’s one quite practical thing: when I make music, I usually have a movie or music videos running on a second screen. It influences the music. I think about sonic choices in visual terms. Like if there’s a harsh bit of silence, that’s like a blackout in a movie. As for the concrete artworks, I don’t make all of them myself. I do the graphics, but if it’s a photo or painting, that’s usually someone else. I do usually think of a concept or a storyline though, so it’s not just like, “Here’s the sound, come up with something.”

I like to contrast the visuals and the sound. If it’s a super cheesy, poppy track, brand it really serious and dry. Maybe sometimes the other way around: if it’s an ambient track, I’ll put a really cute or funny-looking image. That’s what the visuals help with, de- or re-contextualizing the prejudices people might have about certain sounds. If you show someone a seven-minute ambient track with plain gray artwork and tiny text in the corner, they’ll go, “Yeah, I know what this is going to be.” But if it has a funny-looking fish on it we’re cooking.

You’ve been called a minimalist. While that doesn’t seem to describe this new project, the efficiency with which you use sounds is striking. Do you think of yourself as a minimalist at all? Do you like that term?

I think that minimalist thing probably comes from my first couple of EPs. They were almost dogmatic. It would be one synthesizer only, no drums. Now it’s different. A friend of mine, Lorenzo Senni — a composer and producer from Italy who was kind of a mentor when I was younger — coined the term “minimalism on steroids.” Minimalism, but cranked up and fun. I like the word “efficiency” though. It’s more about reducing things to just what you need. I try to never have anything unnecessary in my music.

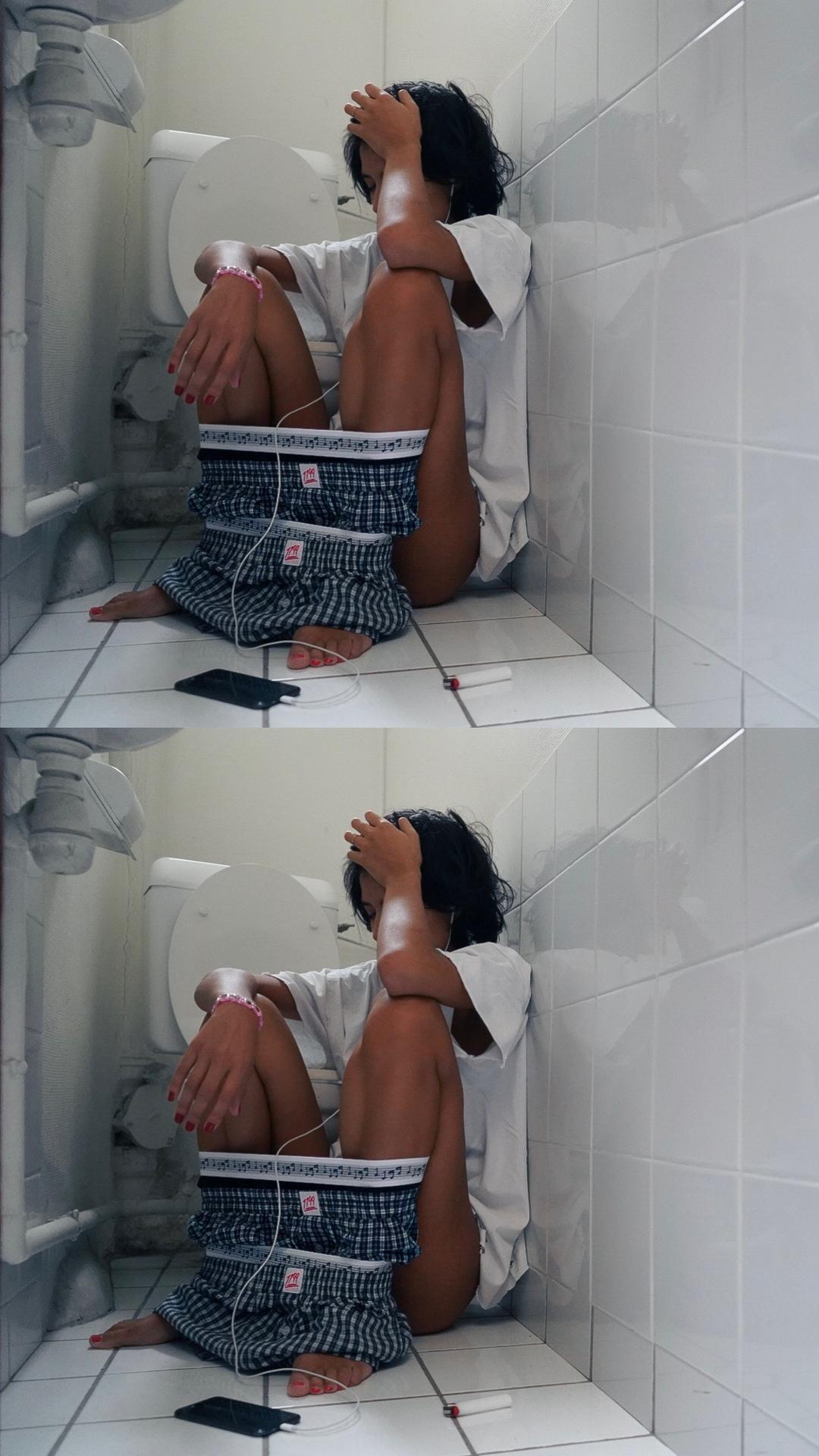

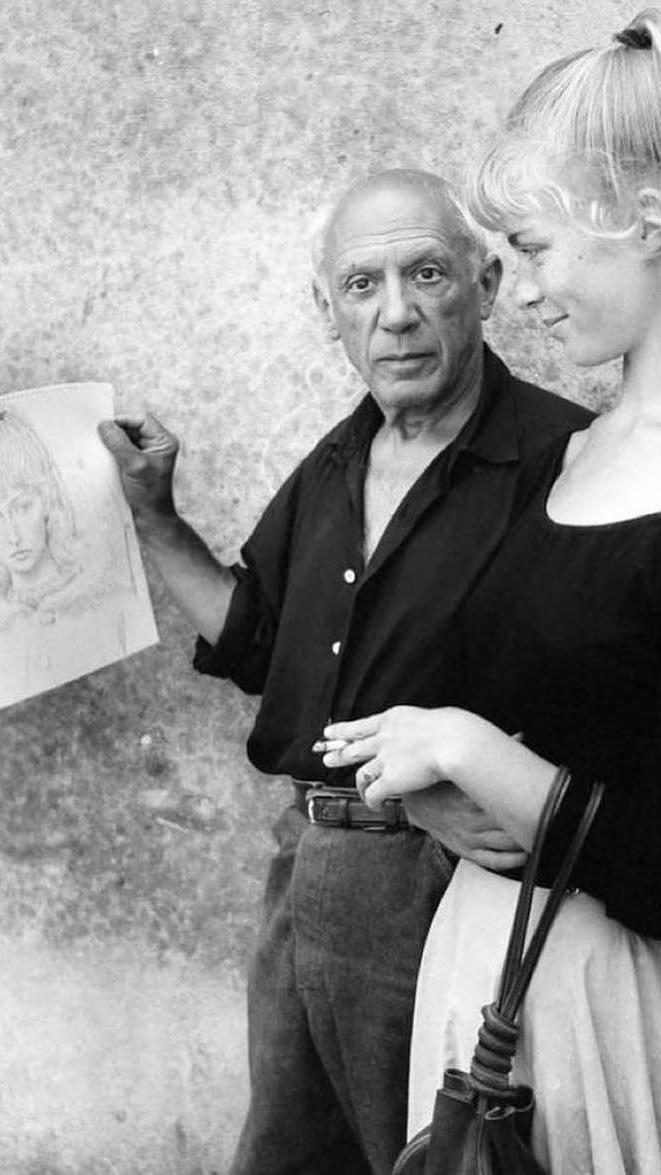

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/22e1783ab9e5a66c3f294164242d154df7b5a78c-1522x1903.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=761)

Mechatok, in his classical guitar days

Where do you go when you need inspiration? This could be a physical place or specific artists or pieces of art you look at.

Rather than observing my own bubble, I like looking at the most popular culture. Being an artist like this, it’s easy to get caught up in your scene. The popular stuff sometimes feels exotic and weird compared to what you're used to. So like when I started out, DJ Mustard was the most inspiring thing. You might laugh, but he always managed this absurd, architectural structure — four columns and a roof, three notes and a snap. Nothing unnecessary. Stuff like that always inspired me. Now, it’s watching K-pop videos with a different shot every second and five-section songs. That rush of fast culture is what gets me excited to make something. It sparks a drive — I want to compete with this, but I most likely won’t be able to. But I’ll probably still like the result of the attempt.

There’s kind of an almost moral panic that some people have about pop culture and super popular things. That can be an elitist way to look at the world. Maybe it’s good to open up to it.

The way I’d look at it—this isn’t true for everybody—but most of the art that really hits for me, whether it’s music, movies, whatever, is stuff that manages to both capture, comment on, and embody something that’s super contemporary and relatable. I’m not interested in blind complicity, just playing the game or doing business. That’s fine, but what I think is really interesting is an almost documentary way of looking at pop. Documentaries are manipulative. It’s all about how you frame what’s already there. So to me, that’s where the moral question kind of goes out the window. I’m not saying I’m siding with it; I’m saying, “This is just what’s going on,” as far as I can be objective about it. Which I can’t.

What makes you happy?

Honestly, the most serene state I can be in is in transit. That might change with age, but usually, when I’m in one place—physically or mentally—for too long, I get frustrated. So I’m happiest sitting on a train watching things go by, or on a plane or something. That’s really the calmest my brain can be. There’s nothing you can do—you’re stuck in this thing, it's moving at hundreds of kilometers an hour, and that’s it.

Are you hopeful about the future?

I’m clearly a hopeful person—otherwise I probably wouldn’t have the ambition to keep going. There are plenty of reasons not to be hopeful right now too. What makes me hopeful in my own personal life is that I can do this music thing. It’s a privilege. But I can’t make this point without acknowledging that we’re also going through some of the worst conflicts we’ve ever seen. It’s a bleak time. But I wouldn’t say it’s an entirely bad time for culture. Maybe that’s just an excuse to stay hopeful though.

Interview and intro by Noah Jordan (@nnoahaonn)